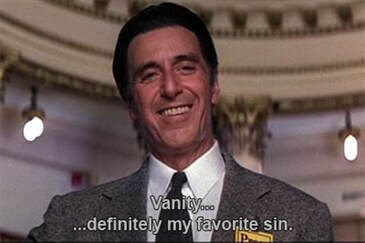

…אֵ֜לֶּה מַסְעֵ֣י בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר יָצְא֛וּ מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם These are the journeys of the Children of Israel who went out from the land of Egypt… The parshah begins with Moses writing down the origin story of the children of Israel, beginning with the Exodus from Egypt and recounting all the places they visited and battles they engaged up to that point. It then goes on to instruct what they should do once they enter the land – how they should conquer the land, how they should divide the land between the tribes, and so on. As the last parshah leading into the last book of the Torah, it functions to give context and define the identity of the Israelites: “This is where you come from, this is where you’re going, and this is what you have to do…” The implication is that identity and story are important; they give us direction and definition. And yet, in Pirkei Avot 3:1, we find a passage that seems to contradict this principle: עֲקַבְיָא בֶן מַהֲלַלְאֵל אוֹמֵר ... דַּע מֵאַיִן בָּאתָ, וּלְאָן אַתָּה הוֹלֵךְ, ... מֵאַיִן בָּאתָ, מִטִּפָּה סְרוּחָה, וּלְאָן אַתָּה הוֹלֵךְ, לִמְקוֹם עָפָר רִמָּה וְתוֹלֵעָה... Akavyah ben Mahalalel said: “... Know from where you come, and where you are going... From where do you come? From a putrid drop. Where are you going? To a place of dust, worms and maggots...” While this passage seems to begin with the same premise, advising to “know from where you come and where you are going,” the answers it gives seem to have the opposite effect from the parshah; there is no special identity of having overcome slavery and become a holy people, no promised land, just the harsh biological facts: you’re going to a “place of dust, worms and maggots.” Ugh! The first passage tells us who are; it tells us we are something; the second knocks down our stories; it tells us we are nothing. There are two Hebrew words that are sometimes translated as nothing: ayin and hevel, with opposite implications. Ayin is actually the spiritual goal: to realize the dimension of our own being that is “no-thing-ness” beyond all form. This is the open space of awareness itself, boundless and free. The Tanya points out that while we tend to think of the splitting of the Red Sea to be a great miracle, the far greater miracle is that there is a sea at all, that there is anything at all. The splitting of the sea was merely a manipulation of something that was already there, but the fact of existence itself is a bringing forth of yesh me’ayin, Something from Nothing. The Maggid of Metzritch took this even further, saying that as great as the creation of the universe is yesh me’ayin, Something from Nothing, even greater is our task: to transform the Something back to the Nothing – ayin me’yesh! Meaning: right now, as you read these words, the words are a something. You perceive the something, but what is it that perceives? The awareness that perceives is literally no-thing; it is that which perceives all particular things – all sensations, all sensory perceptions, all feelings, all thoughts. This is the ayin inherent in our own being, as well as the underlying Presence of Existence, also called the Divine Presence, inherent in all things. These two are not even separate, because everything we perceive arises within and is made out of nothing but awareness, and the awareness that we are is the awareness of Existence Itself, looking through our eyes, hearing through our ears. The other word for “nothing,” which has a negative implication, is hevel. Hevel could be translated as nothingness, futility, emptiness, or vanity. הֲבֵ֤ל הֲבָלִים֙ אָמַ֣ר קֹהֶ֔לֶת הֲבֵ֥ל הֲבָלִ֖ים הַכֹּ֥ל הָֽבֶל׃ Hevel havalim – vanity of vanities –said Kohelet — vanity of vanities, all is vanity! This famous opening line from Ecclesiastes springs from King Solomon’s disillusionment with all his experiences and accomplishments. He had everything, and could do anything he wanted – and yet, all was nothingness; everything comes and goes, a time for this and a time for that, nothing is really new, nothing really satisfies. The same word is used in the haftora: כֹּ֣ה ׀ אָמַ֣ר יְהוָ֗ה מַה־מָּצְא֨וּ אֲבוֹתֵיכֶ֥ם בִּי֙ עָ֔וֶל כִּ֥י רָחֲק֖וּ מֵעָלָ֑י וַיֵּֽלְכ֛וּ אַחֲרֵ֥י הַהֶ֖בֶל וַיֶּהְבָּֽלוּ׃ Thus says the Divine: What did your ancestors find in Me that was wrong, that they distanced themselves from Me and went after nothingness (hevel), and became nothingness? Both these passages point to our human condition: we tend to make much of the hevel, running after this and away from that, but it is all for naught; we are going to “place of dust, worms and maggots.” The meanings of these two words for nothing are also implied by the letters from which they are composed. Every Hebrew letter has certain meaning. Ayin is אין alef, yod, nun. Alef represents Oneness, yod represents simple awareness, and nun represents impermanence. So, we can see ayin as: "All things come and go (nun), but behind this is the awareness (yod) of the Oneness (aleph)." Hevel is הבל hei, bet, lamed. Hei represents the breath, bet means "house" and begins the word bonei which means "build," and lamed means "learn." So, hevel can be understood as: Learning (lamed) that whatever is built (bet) is passing like wind (hei). This kind of learning is the path that leads to the Divine, that leads to Wholeness, that leads from the hevel to the ayin. As the last line of Ecclesiastes says: ס֥וֹף דָּבָ֖ר הַכֹּ֣ל נִשְׁמָ֑ע אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִ֤ים יְרָא֙ וְאֶת־מִצְותָ֣יו שְׁמ֔וֹר כִּי־זֶ֖ה כָּל־הָאָדָֽם׃ The end of the matter, when all is perceived: Be aware of the Divine and guard the mitzvot! For this is the Whole Person. Be aware of the Divine – that is, know the ayin that underlies everything, the ayin that is perceiving, right now. Guard the mitzvot – that is, don’t act from the motive of running after or away from the hevel, act from the place of love, act from the place of connection to the ayin from which all springs and to which all will return. Make That your identity: …אֵ֜לֶּה מַסְעֵ֣י בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר יָצְא֛וּ מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם These are the journeys of the Children of Israel who went out from the land of Egypt… The Divine has brought you to this moment to realize your inner freedom and has given you the only important choice there is, in this moment: to turn from the hevel of ego to the underlying ayin of your deepest nature, right now. Once there was a rabbi who was davening (praying) with great intensity toward the end of Yom Kippur, when he suddenly became overwhelmed with the realization of how attached to vanity, to hevel, he had become. “Ribono Shel Olam! Master of the universe!” he cried out, “I am nothing! I am nothing!” When the hazzan (the cantor) saw him do this, he too became inspired and cried out as well: “Ribono Shel Olam! I am nothing! I am nothing!” The truth was infectious. Suddenly, a poor congregant, Shmully the shoemaker, also became deeply moved and exclaimed as well: “Ribono Shel Olam! I am nothing! I am nothing!” When the hazzan saw Shmully’s enthusiasm, he turned to the rabbi with incredulity: “Look who thinks he’s nothing!”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed