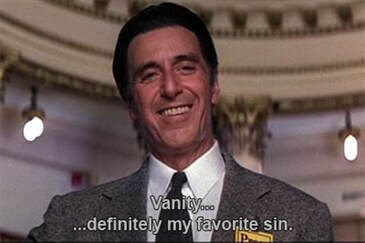

…אֵ֜לֶּה מַסְעֵ֣י בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר יָצְא֛וּ מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם These are the journeys of the Children of Israel who went out from the land of Egypt… The parshah begins with Moses writing down the origin story of the children of Israel, beginning with the Exodus from Egypt and recounting all the places they visited and battles they engaged up to that point. It then goes on to instruct what they should do once they enter the land – how they should conquer the land, how they should divide the land between the tribes, and so on. As the last parshah leading into the last book of the Torah, it functions to give context and define the identity of the Israelites: “This is where you come from, this is where you’re going, and this is what you have to do…” The implication is that identity and story are important; they give us direction and definition. And yet, in Pirkei Avot 3:1, we find a passage that seems to contradict this principle: עֲקַבְיָא בֶן מַהֲלַלְאֵל אוֹמֵר ... דַּע מֵאַיִן בָּאתָ, וּלְאָן אַתָּה הוֹלֵךְ, ... מֵאַיִן בָּאתָ, מִטִּפָּה סְרוּחָה, וּלְאָן אַתָּה הוֹלֵךְ, לִמְקוֹם עָפָר רִמָּה וְתוֹלֵעָה... Akavyah ben Mahalalel said: “... Know from where you come, and where you are going... From where do you come? From a putrid drop. Where are you going? To a place of dust, worms and maggots...” While this passage seems to begin with the same premise, advising to “know from where you come and where you are going,” the answers it gives seem to have the opposite effect from the parshah; there is no special identity of having overcome slavery and become a holy people, no promised land, just the harsh biological facts: you’re going to a “place of dust, worms and maggots.” Ugh! The first passage tells us who are; it tells us we are something; the second knocks down our stories; it tells us we are nothing. There are two Hebrew words that are sometimes translated as nothing: ayin and hevel, with opposite implications. Ayin is actually the spiritual goal: to realize the dimension of our own being that is “no-thing-ness” beyond all form. This is the open space of awareness itself, boundless and free. The Tanya points out that while we tend to think of the splitting of the Red Sea to be a great miracle, the far greater miracle is that there is a sea at all, that there is anything at all. The splitting of the sea was merely a manipulation of something that was already there, but the fact of existence itself is a bringing forth of yesh me’ayin, Something from Nothing. The Maggid of Metzritch took this even further, saying that as great as the creation of the universe is yesh me’ayin, Something from Nothing, even greater is our task: to transform the Something back to the Nothing – ayin me’yesh! Meaning: right now, as you read these words, the words are a something. You perceive the something, but what is it that perceives? The awareness that perceives is literally no-thing; it is that which perceives all particular things – all sensations, all sensory perceptions, all feelings, all thoughts. This is the ayin inherent in our own being, as well as the underlying Presence of Existence, also called the Divine Presence, inherent in all things. These two are not even separate, because everything we perceive arises within and is made out of nothing but awareness, and the awareness that we are is the awareness of Existence Itself, looking through our eyes, hearing through our ears. The other word for “nothing,” which has a negative implication, is hevel. Hevel could be translated as nothingness, futility, emptiness, or vanity. הֲבֵ֤ל הֲבָלִים֙ אָמַ֣ר קֹהֶ֔לֶת הֲבֵ֥ל הֲבָלִ֖ים הַכֹּ֥ל הָֽבֶל׃ Hevel havalim – vanity of vanities –said Kohelet — vanity of vanities, all is vanity! This famous opening line from Ecclesiastes springs from King Solomon’s disillusionment with all his experiences and accomplishments. He had everything, and could do anything he wanted – and yet, all was nothingness; everything comes and goes, a time for this and a time for that, nothing is really new, nothing really satisfies. The same word is used in the haftora: כֹּ֣ה ׀ אָמַ֣ר יְהוָ֗ה מַה־מָּצְא֨וּ אֲבוֹתֵיכֶ֥ם בִּי֙ עָ֔וֶל כִּ֥י רָחֲק֖וּ מֵעָלָ֑י וַיֵּֽלְכ֛וּ אַחֲרֵ֥י הַהֶ֖בֶל וַיֶּהְבָּֽלוּ׃ Thus says the Divine: What did your ancestors find in Me that was wrong, that they distanced themselves from Me and went after nothingness (hevel), and became nothingness? Both these passages point to our human condition: we tend to make much of the hevel, running after this and away from that, but it is all for naught; we are going to “place of dust, worms and maggots.” The meanings of these two words for nothing are also implied by the letters from which they are composed. Every Hebrew letter has certain meaning. Ayin is אין alef, yod, nun. Alef represents Oneness, yod represents simple awareness, and nun represents impermanence. So, we can see ayin as: "All things come and go (nun), but behind this is the awareness (yod) of the Oneness (aleph)." Hevel is הבל hei, bet, lamed. Hei represents the breath, bet means "house" and begins the word bonei which means "build," and lamed means "learn." So, hevel can be understood as: Learning (lamed) that whatever is built (bet) is passing like wind (hei). This kind of learning is the path that leads to the Divine, that leads to Wholeness, that leads from the hevel to the ayin. As the last line of Ecclesiastes says: ס֥וֹף דָּבָ֖ר הַכֹּ֣ל נִשְׁמָ֑ע אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִ֤ים יְרָא֙ וְאֶת־מִצְותָ֣יו שְׁמ֔וֹר כִּי־זֶ֖ה כָּל־הָאָדָֽם׃ The end of the matter, when all is perceived: Be aware of the Divine and guard the mitzvot! For this is the Whole Person. Be aware of the Divine – that is, know the ayin that underlies everything, the ayin that is perceiving, right now. Guard the mitzvot – that is, don’t act from the motive of running after or away from the hevel, act from the place of love, act from the place of connection to the ayin from which all springs and to which all will return. Make That your identity: …אֵ֜לֶּה מַסְעֵ֣י בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר יָצְא֛וּ מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם These are the journeys of the Children of Israel who went out from the land of Egypt… The Divine has brought you to this moment to realize your inner freedom and has given you the only important choice there is, in this moment: to turn from the hevel of ego to the underlying ayin of your deepest nature, right now. Once there was a rabbi who was davening (praying) with great intensity toward the end of Yom Kippur, when he suddenly became overwhelmed with the realization of how attached to vanity, to hevel, he had become. “Ribono Shel Olam! Master of the universe!” he cried out, “I am nothing! I am nothing!” When the hazzan (the cantor) saw him do this, he too became inspired and cried out as well: “Ribono Shel Olam! I am nothing! I am nothing!” The truth was infectious. Suddenly, a poor congregant, Shmully the shoemaker, also became deeply moved and exclaimed as well: “Ribono Shel Olam! I am nothing! I am nothing!” When the hazzan saw Shmully’s enthusiasm, he turned to the rabbi with incredulity: “Look who thinks he’s nothing!”

0 Comments

Today it seems that, once again, we are in a cultural and political crisis. Beliefs and values seem to have clumped together into two opposing camps, each often accusing the other of the worst. It is a war, in a sense, because the prevailing belief is that if you hear the point of the other and empathize in any way, they might get the upper hand. So, the rule is, fight to win. Exaggerate (or invent) the failings of the other, so that they remain your enemy. I wonder if it is possible for intelligence to pierce through this mind and emotion created illusion, just as the spear of Pinhas pierced through Zimri and Kozbi (names which together mean the “song of falsehood”)? Can awareness prevail over the power of ideology, on a cultural level? Can we, not only as individuals, but as a movement in history, become more interested in questions than assertions? It is true, questions can be endless, and sometimes action is required. If an arrow is stuck in your body, you don’t ask where the arrow came from, who made it, and so on; you remove it from your body and save your life. But what about when the action we think is required isn’t based on a clear seeing of an arrow in your body, but on stories we believe in, stories we identify with, stories that our collective egos are invested in? It is then, perhaps, that the action required is a stepping back from acting to make a space for questions. It is then, perhaps, that the actions required would be actions aimed at awakening the spirit of the question in people. Then, perhaps, is now. I wonder: might we be able to ask questions that pierce through our most cherished beliefs about what is right and true, in order to clear a space for seeing without bias? Or, at least, might we be able to see our own bias? I know, these are dangerous questions, and it is dangerous to promote the spirit of the question. Many in history have been killed for doing so. In the haftora, Elijah must have felt the danger and hopelessness of his mission in a similar way, when Jezebel vowed to have him killed for questioning the cult of Baal that the Israelites had adopted. Despondent, he left the world of people and went out into the wilderness to die. But then an angel came to him and gave him food and drink – “get up and eat!” He ate and drank a little, then lay back down again to die. Then the angel gave him some more food: “You will need this for your journey ahead!” Then he seems to get super powers from the second meal and he walks for forty days and nights. Eventually he comes to a cave here he is shown a vision of the power of the Divine, manifesting as great winds, earthquakes and fires, and yet the Divine was not in the wind, the earth, or the fire. Where was It? ק֖וֹל דְּמָמָ֥ה דַקָּֽה – Kol d’mama dakah – a still, small voice… Can we sense the Divine power in the fiery storms that are erupting today? Can we sense that we are being pushed by them, as the forces of evolution have always pushed life to transform, to hear what is beneath all those storms? Can the kol d’mama dakah actually be our own voice, arising out of the depths of stillness beneath our thoughts and feelings? The angel is tapping you on the shoulder; she gives you the nourishment of the teachings and implores you: don’t run away from the storms, but don’t get caught up in them either! God is not in the storm, but there is a Divine potential of the storm – this crisis has a purpose, if we are willing to engage it. And that purpose could be: awakening out of the mind, out of the passionate beliefs, out of ideologies, out of polarization, and into the spirit of the question, into the spirit of openness, into the willingness to really look. Whether that is the purpose or not, is actually our choice. Will you be part of the (r)evolution? More on Parshat Pinhas... Freedom in Pain – Parshat Pinhas

7/5/2018 1 Comment There are really two different kinds of discomfort. The first is like when you stub your toe. It happens suddenly, and once it happens, you're going to feel pain; there's no choice involved. The second is like when someone is talking your ear off, and you want to get away. The discomfort increases moment by moment, and you can get away any time you choose. If you want to live an awakened life, if you want to be free, these two kinds of discomfort require two different responses. The first requires simple acceptance; there's no way to escape the intense pain once you stub your toe. The second requires conscious choice about when to stay in the discomfort and keep listening to the person talk at you, and when to simply walk away. Yet for some reason, we often confuse these two situations. We can trick ourselves into thinking we're "trapped" by someone talking to us, and not realize that we have a choice. When we finally escape, we might be angry at the person: "How could they keep talking at me like that! How insensitive!" And yet, we could have left any time; we don't take the power that's ours, and instead blame someone outside ourselves for our experience. Or, we lament and complain about some discomfort that we can't control, when we should really just accept it; it already happened, we have no control! So why be in conflict with it? There's a hint of this in Parshat Pinhas: צַ֚ו אֶת־בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל וְאָֽמַרְתָּ֖ אֲלֵהֶ֑ם אֶת־קָרְבָּנִ֨י לַחְמִ֜י לְאִשַּׁ֗י רֵ֚יחַ נִֽיחֹחִ֔י תִּשְׁמְר֕וּ לְהַקְרִ֥יב לִ֖י בְּמֽוֹעֲדֽוֹ Command the children of Israel and say to them, “My offerings, My food for My fires, My satisfying aroma, you shall take care to offer Me in its special time… If you draw your awareness into your pain, it becomes לַחְמִ֜י לְאִשַּׁ֗י – food for My fires –that is, food for awareness, because awareness is strengthened through the practice of fully being present with whatever you feel the impulse to resist. That's the first kind of pain, like stubbing your toe. That’s why the offering is called קָרְבָּנִ֨י – My korban, because korban means to “draw near.” The magic is that even though you are drawing your awareness into something unpleasant, the attitude of openness can transmute the pain into a connection with the Divine, with Reality, with our own being, which are all ultimately the same thing. The second type of pain, as in the example of someone talking at you, is the רֵ֚יחַ נִֽיחֹחִ֔י –pleasing aroma. That's because there's a sweetness when you claim your own power to change your situation, and not blame others. Our response to these different kinds of discomfort must be done בְּמֽוֹעֲדֽוֹ – it its special time – meaning, our response has to be in alignment with the reality of our situation. Is it time to simply accept, or is it time to act? Notice the inner tendency to lean away from your own power, or to lean into resisting what has already happened. Then, simply lean a bit the other way, and come back into balance. Once, when Reb Yisrael of Rizhyn was sitting casually with his Hassidim and smoking his pipe, one of them asked, "Rebbe, please tell, me– how can I truly serve Hashem?" "How should I know?" said the rebbe, "But I'll tell you, once there were two friends who broke the law and were brought before the king. The king was fond of them and wanted to acquit them, but he couldn't just let them off the hook completely. "So, the king had a tight rope extended over a deep pit. He told the friends, 'If you can get to the other side of the pit on the tightrope, you can go free.' The first set his foot on the rope and quickly scampered across. The second called to his friend, 'How did you do it?' "'How should I know?' said the first, 'But I'll tell you– when I started to fall toward one side, I just leaned a little to the other side...'" Good Shabbos! Piercing the Two Layers of Mind- Parshat Pinhas 7/14/2017 0 Comments "Notein lo et briti shalom – "I give him my covenant of peace.” Parshat Pinkhas begins in the aftermath of a plague that God put on the Israelites, because they had been seduced by the Midianites into an idolatrous orgy. At its climax, The Israelite man Zimri and the Midianite woman Kozbi are engaged in sexual union in front of everyone, and the zealot Pinkhas comes along and kills them both by piercing them through with a spear, causing the punishing plague to subside. God then says in the opening of the parsha, that Pinkhas “heishiv et khamati- turned back my wrath from upon the children of Israel- b’kano et kinati- when he avenged my vengeance” or “my jealousy. Therefore, hin’ni, check it out- notein lo et briti shalom- I give him my covenant of peace.” Woe, what is going on here. This sounds like the vengeful, jealous God that everyone loves to hate. What kind of a God is that, right? A God that’s jealous, a God that kills people and so on. And yet, in a sense, that’s actually perfectly true. From a certain point of view, God is a vengeful, jealous God that kills people. Not literally, of course, but this is scripture. It’s pointing to something spiritual in the language of the time it was written. So what is it pointing to? There is a basis, or a foundation for everything you’re experiencing right now. Whether we’re talking about things that appear to be outside of you – like the sensory world, what you see, what you hear, or things that appear to be inside you, such as feelings or thoughts, everything is perceived only because of this miracle called consciousness. And in the field of your experience, everything you perceive is, in fact, made out of consciousness. So that thing that I see over there is nothing but consciousness, because seeing is a function of consciousness. And, in fact, the sense of “me” that sees the thing over there, this body/mind that I call me, is also something that I perceive, so it too is just a form of consciousness. So the thing I see and the me that sees are both forms of one consciousness. And yet, as you know, most people have no sense of that at all. There’s just the sense of me over here in this body and that thing over there that I see. Why? Because we’re constantly framing our experience with language that reinforces the belief that things are objective and separate. The language we use refers to “me” and “that thing over there,” and so our thinking which is largely made out of language, is deeply conditioned with this assumption of separateness, even though our experience right now tells us otherwise. But to really see what our experience is telling us, we have to pierce a hole through the lie that’s created with our language. And to do that takes a special effort because the language lie is two-ply. Just like good toilet paper. If you have only one-ply toilet paper, that doesn’t work too well. Good toilet paper has two layers of paper so that it doesn’t tear when you’re using it. It’s the same with our minds- there’s two layers. The first layer is simply the fact that our minds are constantly going. Bla bla bla bla. It’s like a song that you get stuck in your head. Once that song is stuck, it just repeats over and over, because it’s created a groove in your nervous system. That’s why music is groovy. Dance music is always talking about “getting into the groove” and “making you move” because it’s playing on this tendency of the mind to get into grooves of thought patterns within which your mind moves. That’s the first layer you have to get through- the movement in the groove of constant thinking. The other ply is the content of the groove- the nature of how language tends to work. How does language work? Well even right now as I talk about language, the words are creating the impression that language is this thing that “I” am talking about. So there’s the sense that “I” and the subject of this talk, language, are two separate things. This doesn’t get questioned unless we deliberately decide to question it, which is what we’re doing right now by the way, because it’s simply the background assumption of language and thinking- that there’s a me who thinks and talks, and there are things that the “me” thinks and talks about. And yet we can, if we choose, notice that these words right now, as well as whatever concepts we’re talking about, as well as this body that’s talking, as well as the “you” that’s listening, are all living within and are forms of awareness. And as soon as we point this out, there can be this subtle but profound shift- and this is the shift into knowing that there’s only one thing going on. Hashem Eloheinu Hashem Ekhad- All Existence, all Being is not separate from Eloheinu- our own divinity, meaning consciousness, and Hashem Ekhad- All Existence is just this One thing that’s going on- consciousness in form. And how do you know this? Because you are Sh’ma- you are the listening, the perceiving, and nothing you perceive is separate from that. Isn’t it funny that we tend to look for God, thinking we know the world but we have to find God, when in Reality, God is the only thing we really know? Meaning, we know that there’s Existence. And we know that the knowing and the Existence, are not separate. That’s Hashem Ekhad; that’s the Oneness of God right there. Or should we say, right here. So if you choose to think in this very different, very counter-intuitive and yet very obvious kind of way, you can pierce through that ply of separateness almost instantly. Because even though it’s counterintuitive, it’s also really obvious. It’s really obvious that there’s only one Reality and this is it. How many Realities could there possibly be? Only one, because Reality just means whatever is. And it’s also totally obvious that you don’t have to go anywhere or do anything to find Reality, because there’s only ever one place to find it, and that’s always right now in your present moment experience. So once you do that, and hopefully we just did it, the next step is to connect with the Presence of Being in form. Meaning, let your awareness really connect whatever is present, rather than continue with all that duality producing language. Just let yourself be present. This isn’t complicated- just notice what’s going on… and be conscious of your breathing. And in doing that, your mind effortlessly becomes quiet, and you pierce through the other ply- the layer of the constantly moving mind. So once you’ve gotten through the two layers, and maybe you just have, Reality can be your friend, and the plague, so to speak, can be lifted. What’s the plague? It’s just the belief that you’re separate. And that’s why God can be thought of as jealous or vengeful. Not literally of course, but if you’re not paying attention to God, meaning you’re not seeing the underlying Being of everything, always focused on the conditional world, then you’re literally in exile from yourself. You’re identified with this tiny piece of who you really are, and you don’t even know it. So this is why God gives Pinkhas the covenant of shalom – of peace and wholeness – for killing Zimriand Kozbi. Because what is Zimri? It’s like the word zemer- song. So Zimri is “my song”- meaning, the constant movement of the mind; the song that my thoughts are always singing. And what is Kozbi? Kaf-Zayin-Bet means a lie, a falsehood. So Kozbi means “my lie.” And when Zimri and Kozbi unite, that’s the two ply barrier of both constant thinking and the lie of separateness that Pinkhas is able to pierce through. Now, what is Pinkhas? It’s Pey-Nekhs. Pey is a mouth, and Nekhs is bad, or unsuccessful. So Pinkhas knows the bad side of the mouth, meaning language, how it tends to make us unsuccessful in our quest for Truth. So he pierces through both layers, and receives the Brit Shalom, reminding us that whoever wants real peace and wholeness, must also pierce through the two-ply toilet paper of the mind. So on this Shabbat Pinkhas, which we might call the Sabbath of Silence, may we pierce more deeply and consistently through the noise and conditioning of the mind, connecting with and also embodying in our actions, words and even thoughts, the Divine Presence of Being that is ever-present... love, brian yosef Put Your Weed in There! Parshat Pinhas 7/28/2016 4 Comments One of my favorite Saturday Night Live sketches begins in one of those exotic import stores, filled with incense holders, meditation bowls, handmade musical instruments and the like. A stoner-type guy who works there comes up to some customers and starts showing them some crafty knick-knack import. He says in a stoner voice: “This is a Senegalese lute carved from deer wood, used for fertility rituals… oh and you can put your weed in there!” They move from one knick-knack to another. Each time the stoner guy describes the intricacies and history of the item, he concludes by showing them some hole or little compartment in it and says, “Oh, and you can put your weed in there!”- and stuffs a baggy of marijuana into it. Finally, a cop comes into the store. When the stoner sees the cop, he anxiously tells his customers to say nothing about weed. The cop walks over to them and says, “How you doing?” The stoner clenches his jaw, trying to restrain himself, and then busts out uncontrollably: “WEED!! WEED!! WEED!!” The cop says, “Why are you yelling like that?” He then examines the knick-knack he’s holding, finds the weed and arrests him. The Talmud says (Sukkah 52a), “A person’s yetzer (drive, inclination, desire) grows stronger each day and desires his death.” In the sketch, all the stoner guy has to do to not get caught is nothing. But he can’t help it- he yells, “Weed! Weed!” How often are you given the opportunity for life to go well, to go smoothly, and somehow you find yourself messing the whole thing up? Why do we have this yetzer hara- this “evil urge”- this drive toward self-destruction? In his introduction to Pirkei Avot, HaRav Yochanan Zweig proposes something unique and compelling: He says that the reason we tend to sabotage ourselves is actually because of our unbelievably enormous potential. We know, on some level, that our potential is enormous, and that creates a kind of psychological pressure. We are terrified of not living up to our potential. So, to avoid the pain of knowing our great potential and not living up to it, we try to convince ourselves that we have no potential, that we are worthless, and all our self-destructive behaviors are aimed at proving our worthlessness to ourselves. This week’s reading begins with the aftermath of a self-destructive incident as well. The Israelites had just been dwelling peacefully in their camp. Then the Midianites come along and try to seduce them into an orgy of idolatry and adultery. The Midianites didn’t attack them militarily; all the Israelites had to do is say “No thank you,” and they’d be fine. But what happens? They are easily seduced and the Divine wrath flares up. It’s the golden calf all over again! Dang. The fellow for whom the parshah is named, Pinhas, then wields his spear and kills two particularly hutzpadik offenders who were flaunting their orgiastic idolatry right in front of the holy “Tent of Meeting.” This week’s parshah then begins with Pinhas getting rewarded for his heroic murder, and he is given a Divine Brit Shalom- a “Covenant of Peace.” For many, it’s hard to see anything positive in this story. Murder in the name of religious zealotry? Embarrassing. And yet, if we dig deep into the underlying currents of the narrative, an urgent message emerges: There is a powerful drive toward self-sabotage, toward self-destruction. It is seductive, sexy, exciting and relentless. It will disguise itself in all kinds of ways to trick you and lure you into its power. But, you can overcome it, if you are aware of it! In fact, if you are aware of it, it has no power at all. The Talmud says that in the future, the Yetzer harawill be revealed for what it really is. When the wicked see the yetzer hara, it will appear as a thin hair. They will weep and say, “How were we ensnared by such a thin hair?” The key is being conscious, and clearly holding the intention that you are not living for your own gratification, but rather you are here to serve the enormous potential for wisdom and love that is your essence, your divine nature. At the same time, it’s crucial to acknowledge that you do have needs and desires. While it’s true there are times when our impulses are so destructive that they must be completely halted as represented by Pinhas and his spear, in most cases our thirsts can be quenched in moderation, with balance and wisdom. Our desires, after all, are like the impulses of an animal. Don’t let the animal take over, but don’t torture it either. You have the power, through your awareness, to give the animal enough so that it let’s you have peace, without it taking over and pulling you toward self-sabotage. There’s a story of a simple man who came to Maggid of Koznitz with his wife, demanding that he be allowed to divorce her. “Why would you want to do that?” asked the Maggid. “I work very hard all week,” said the man, “and on Shabbos I want to have some pleasure. Now for Shabbat dinner, my wife first serves the fish, then the onions, then some heavy main dish, and by the time she puts the pudding on the table, I have eaten all I want and have no appetite for it. All week I work for this pudding, and when it comes I can’t even taste it- and all my labor was for nothing! “Time after time I ask my wife to please put the pudding on the table right after Kiddush (the blessing over wine), but no! She says that the way she does it is the proper minhag (custom).” The Maggid turned to the woman. “From now on, make a little extra pudding. Take a bit of the pudding and serve it right after Kiddush.Then, serve the rest of it after the main dish, as before.” The couple agreed to this and went on their way. From that time on, it became the minhag (custom) in the Maggid’s house to serve some pudding right after Kiddush, and this minhag was passed on to his children and his children’s children. It was called the Shalom Bayit Pudding- the “Peace-in-the-House Pudding!” On this Shabbat Pinkhas, the Sabbath of Peace, may we be aware of the needs of our hearts an bodies, giving and receiving the pleasures of life without being controlled by them. May we know that we are infinitely more vast than any particular impulse or want. May we see that all impulses come and go, and that we need not identify with them. And that is the good kind of self-destruction! Good Shabbos, Bless you, brian yosef

…כְּגַנֹּ֖ת עֲלֵ֣י נָהָ֑ר… כַּאֲרָזִ֖ים עֲלֵי־מָֽיִם׃ יִֽזַּל־מַ֙יִם֙ מִדָּ֣לְיָ֔ו וְזַרְע֖וֹ בְּמַ֣יִם רַבִּ֑ים Like gardens by a river… like cedars by water, their boughs drip with moisture, their roots have abundant water… (Numbers 24:6) Water is such a powerful metaphor for consciousness because it is so fundamental – not only is it an essential nutrient that makes up about 70% of our bodies, but it is also the medium through which we are cleansed of both inner and outer schmutz. Similarly, just as our bodies are made primarily out of water, on the level of consciousness, we are fundamentally made out of awareness. And just as our physical bodies become polluted and must be regularly purified with the help of water, so too we are affected by every experience – everything that happens to us, every emotion we feel, every thought that arises. We are, in a sense, like sponges, absorbing the energies of all that we experience, constantly. Fortunately, just like a sponge that is cleansed through water, so too we can get clean from experience with the help of awareness. Whatever we experience, no matter how intense, traumatic, or disappointing, is ultimately not who we really are; it is like schmutz that leaves our consciousness if we know how to rinse, squeeze, and rinse again. And, if we don’t immerse frequently in the waters of awareness, then just like a sponge, we can dry out. The dried-out sponge can neither absorb anything new nor can it be distinguished from all the dried-on schmutz within it. Similarly, when we become “dried out,” our belief systems are frozen; we can’t see anything new, but rather we perceive everything through the screen of our preconceptions. The inner pollution of negativity becomes indistinguishable from who we are. But no matter how dried out and encrusted we might become, just like the sponge, soak it in the water of awareness and the life comes back. If you’re really dried out, it might take some time for the water to penetrate. But once it does, you will know, because all that stuff you thought was you will start rinsing away. מַה־טֹּ֥בוּ אֹהָלֶ֖יךָ יַעֲקֹ֑ב מִשְׁכְּנֹתֶ֖יךָ יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ Mah tovu – How good are your tents, O Jacob, Your dwellings, O Israel! (Numbers 24:5) “Jacob” and “Israel” are the “before” and “after.” At first you may be practicing – meditating, davening, learning – but you still feel like a dried-out sponge, because the waters of awareness haven’t penetrated yet. That’s ohalekha Ya’akov – the “tents of Jacob” – because you’re sitting and working in the “tent” of goal-oriented practice. But eventually, the water breaks through and you get soaked. At that point, just like a sponge you still can get dirty again and again, but you know the dirt isn’t you; you know how to get clean. Then, you can bring that “moisture” of consciousness out of the tent and into more and more of life – that’s mishklanotekha Yisrael – the “dwellings of Israel,” because wherever you are, you can bring that Presence, that Shekhinah, with you. How do you do it? The haftora tells us: הִגִּ֥יד לְךָ֛ אָדָ֖ם מַה־טּ֑וֹב וּמָֽה־יְהוָ֞ה דּוֹרֵ֣שׁ מִמְּךָ֗ You have been told, O human, what is good! Actually, you already know the answer intuitively, but then it tells us again just in case: כִּ֣י אִם־עֲשׂ֤וֹת מִשְׁפָּט֙ וְאַ֣הֲבַת חֶ֔סֶד וְהַצְנֵ֥עַ לֶ֖כֶת עִם־אֱלֹהֶֽיךָ׃ Only to do justice and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your Divinity… On the inner level, asot mishpat – doing justice – means giving your attention fully to all of this moment, not “favoring” some experiences over others, just as a judge would hear all testimonies and not take any bribes. Ahavat hesed – love of kindness means giving your awareness from the heart, not in a cold, mechanical way, but as an expression of generosity and benevolence. Hatzneia lekhet im Eloheikha – walking humbly with your Divinity means being aware of the Mystery, of the limits of your own understanding, and living through your faith in That Mystery, knowing the Divine as the underlying Reality behind all experience… More on Parshat Balak... Open Eye – Parshat Balak

6/27/2018 1 Comment What is the pupil of an eye? The pupil is actually the opening through which pours the light that creates the images we see. The pupil is essentially a hole. The third line of the mystical prayer, Ana B'khoakh, says: “Please, Divine Strength, those who foster Your Oneness, like the pupil of an eye, guard them.” This line is unusual. If we’re asking God to guard us, to keep us safe, why are we likening ourselves to a bavat- a pupil of an eye? It seems like it would make more sense to say, please guard us like a baby, or guard us like a city, but guard us like a pupil? It’s a strange idiom. So let’s go into this a little bit. What is the pupil of an eye? The pupil is actually the opening through which pours the light that creates the images we see. The pupil is essentially a hole. And yet, if you make eye contact with a person, it’s really the pupil of the eye that gives you the sense of eye contact being made. That’s why in all those zombie movies, when they want to make a person seem like they’re dead, they somehow take away the pupils from the actors’ eyes. Maybe they do with special contact lenses, maybe they use CGI, but however they do it, the effect of an eye with no pupil is the effect of there being nobody home. It’s a disturbing image to see a person’s eye with no pupil, because we somehow know intuitively that the pupil indicates consciousness- it indicates that there’s someone there. Which is interesting, because everyone’s pupils look more or less the same. The color of people’s eyes are different, the shape of people’s eyes are different, the face in which the eyes are set is completely unique for each person. You can’t tell the identity of someone by their pupils; you need to see their face. And yet, it’s the pupil that tells you there’s consciousness, that there’s someone home. This fact of the pupil indicating consciousness, on one hand, yet also being nothing but an opening, on the other, is also a great symbol for who we really are. Are we our bodies? No. Are we our faces? No. Are we our feelings? Our thoughts? Our personalities? All of these things are part of us, but none of them are essentially us. The only essential ingredient is consciousness; and like the pupil of your eye, your consciousness is simply an opening. It’s not unique, it’s more or less the same for everyone, and yet it’s the most miraculous and precious thing. Without consciousness, everything else is just a shell; just a bundle of patterns. So this prayer is crying out, in the first line, tatir tzerura- untie the bundle! Meaning, uncover and reveal this essential openness that we are, beneath the bundle of patterns of our bodies, our thoughts and our feelings, so that we can know ourselves as this simple openness, k’vavat- like a pupil. Now there’s a certain paradox of consciousness which is also reflected in the pupil. On one hand, the pupil is a simple openness, taking in the whole image of whatever is being seen. Similarly, consciousness is also the simple openness of experience. So in this moment, you may notice, there’s a richness to your experience- there’s your sensations, your senses, the movement of your breathing, any feelings or emotions that may be vibrating in your body, as well as thoughts that arise, persist for some time, and then dissipate. And all this richness is part of one unfolding experience in the present. And yet, at the same time, when you’re aware of the full richness of experience that’s arising in this moment, there also arises the choice to entertain some things within your experience and to not to entertain other things. For example, some anger arises, or the impulse to judge or complain – and you can notice that it’s there, but not act on it. So on the deepest level, you’re saying “Yes” to it, you’re recognizing that this negative impulse exists in this moment, and that’s perfectly okay, but on the level of choice you can say “No” to it by choosing not to act on it; you just let it be there and then to let it dissipate. On the other hand, an impulse may arise to really listen to the person talking to you, or to be generous in some way, and you may choose to say “Yes” to that impulse on both levels; you say “Yes” first to its existence, just as you would to anything that arises when you’re being present, but you might also say “Yes” to act on it. So on the deepest level of awareness, there’s a single “Yes” to everything that arises in the moment. That’s the akhdut- the Oneness, or non-duality of experience. But on the level of choice, there’s a “Yes” to some things and a “No” to other things; that’s the duality of discernment or wisdom. This truth is also reflected in the metaphor of the pupil, in that we generally have two pupils. So on one hand the pupil is a simple openness to light which creates a single image, a single experience- that’s the akhdut, or Oneness level. And yet, there are two pupils, hinting at the yes and the no, the duality of choice that arises within the akhdut of the present. There’s also a hint of this in the Torah story of Bilam the sorcerer. In Parshat Balak, the king of Moav, whose name is Balak, becomes frightened of all these Israelites who are camping in a nearby valley. So, he sends messengers out to the mysterious, reclusive sorcerer Bilam to request that he put a curse on the Israelites. At first, Bilam refuses. But after several requests, he concedes and rides out on his donkey. Next, there’s a strange and unique passage- one of only two instances in the Torah of talking animals. (The other one is the talking snake in the Garden of Eden). In this passage, Bilam rides out on his donkey through a vineyard, when suddenly an angel appears and blocks his path with sword drawn. But, only the donkey can see the angel; Bilam is oblivious to it. The donkey veers off the path to avoid the sword-wielding angel, and accidentally presses Bilam’sfoot into a wall. Bilam gets angry and hits donkey with a stick, at which point the animal opens her mouth and speaks: “Ma asiti l’kha- “What have I done to you?” Bilam yells back- “Because you mocked me! If I had a sword I’d kill you right now!” Says the donkey- “Am I not your donkey that you’ve ridden until this day? Have I ever done anything like this before?” “No,” says Bilam. Suddenly, Bilam’s eyes are magically “uncovered” and he too sees the angel with the sword. Bilam bows, apologizes and offers to turn back. The angel tells him not to turn back, but he should be careful only say the words that the Divine will place in his mouth to say. So, Bilam goes on his way, and meets up with King Balak, who pleads with Bilam to curse the Israelites. But, every time Bilam opens his mouth, he pronounces blessings instead. King Balak tries again and again to get Bilam to curse, bringing him to different places on a mountain overlooking the Israelite camp, as if that would change something. But every time, it just comes out more blessings. In Bilam’s final blessing, he says, “N’um Bilam, b’no v’or un’um hagever sh’tum ha’ayin- “The words of Bilam son of Beor, the words of the man with an open eye…” “N’um shomea imrei El, asher makhazeh Shaddai, yekhezeh nofel ug’lui einayim- “The words of the one who hears the sayings of God, who sees the vision of Shaddai, while fallen and with uncovered eyes- “Mah tovu ohalekha Yaakov, mishkenotekha Yisrael- “How wonderful are your tents, O Jacob, your dwelling places O Israel…” -and the blessings flow on from there. So what’s going on here? Why is it that Bilam’s donkey perceives the angel before he does, and why do his eyes become “uncovered” as a result of the donkey speaking to him? And, once his eyes are uncovered, how does that allow him to “hear” the Divine voice, transforming curses into blessings? So one way to grasp this passage is to understand that the donkey is your own body. There’s a tendency to take the body for granted, as if it’s just a vehicle to achieve your intentions- like a car, or a donkey that you ride on. But the spiritual potential of your body is to be a temple of Presence – a vessel for the light of your awareness. So at first, Bilam is just hitting his donkey, trying to control it. That’s the ego- selfish, angry, and entitled. But when he starts listening to what the donkey is telling him, then suddenly he can see the angel and hear it speak. Meaning, when you become present with your body, anchoring your awareness in your breathing, then you can clearly see the nature of your impulses that arise, and hear the “angels of your better nature” so to speak. So rather than simply being taken over by yoru impulses, there’s space to really see which which ones are blessings and which are curses. That’s the “uncovering of the eyes” so to speak. There’s an impulse of anger, or an urge to put someone down- you can see that clearly and not be taken over by it. Or, there’s an impulse of love, of supportiveness, of listening- that’s a blessing, and you can choose that. That’s the Yes and the No of being conscious. There’s a story that when Reb Yosef Yitzhak of Lubavitch was four years old, he asked his father, Reb Shalom Ber: “Abba, why do we have two eyes, but only one mouth and one nose?” “Do you know your Hebrew letters?” asked Reb Shalom Ber. “Yes,” replied the boy. “And what is the difference between the letter shin and the letter sin?” continued Reb Shalom. “A shin has a dot on the right side, and the sin on the left.” “Right! Now, the letter shin represents fire, and fire makes the light that we see by. The dots on the right and left are like your two eyes. “Accordingly, fire has two opposite qualities. On one hand, it can give us life by keeping us warm and cooking our food; that’s the right dot. On the other hand, it can burn us; that’s the left dot. “Similarly, there are things you should look at with your right eye, and things you should look at with your left eye. You should see others with your right eye, being warm and loving, but see candy with your left eye, not being taken over by that urge to grab at it!” But to maintain your Presence in your body so as to be aware of your freedom to choose blessing and not curse, you have to be ever-watchful; you have to be on guard constantly. Just as the pupil of an eye- k’vavat- is an open space of perception, so your awareness is also an open space through which you can watchfully guard- shomreim- the movements and sensations of your body with gibor- with strength. And, in so doing, we become dorshei yikhudekha- the ones who foster or tap into the Oneness of Reality, the Oneness of this moment. So let’s chant these words: K’vavat Shomreim. As you sing k’vavat, “like a pupil,” open your hands palms upward, to express the openness and transcendence of awareness. And when you sing Shomreim, “Guard Them,” bring your hands in, palms together, intensifying presence in your body. So k’vavat, open hands and aware of the open spaciousness of awareness beyond the body, the space around your body, then shomreim, bringing in hands and intensifying awareness within the body... Who Is It That Blesses? Parshat Balak 7/6/2017 1 Comment “Ma asiti l’kha- “What have I done to you?” In Parshat Balak, the king of Moav, whose name is Balak, becomes frightened of all these Israelites who are camping in a nearby valley. So, he sends messengers out to the mysterious, reclusive sorcerer Bilam to request that he put a curse on the Israelites. At first, Bilam refuses. But after several requests, he concedes and rides out on his donkey. Next, there’s a strange and unique passage- one of only two instances in the Torah of talking animals. (The other one is the talking snake in the Garden of Eden). In this passage, Bilam rides out on his donkey through a vineyard, when suddenly an angel appears and blocks his path with sword drawn. But, only the donkey can see the angel; Bilam is oblivious to it. The donkey veers off the path to avoid the sword-wielding angel, and accidentally presses Bilam’s foot into a wall. Bilam gets angry and hits donkey with a stick, at which point the animal opens her mouth and speaks: “Ma asiti l’kha- “What have I done to you?” Bilam yells back- “Because you mocked me! If I had a sword I’d kill you right now!” Says the donkey: “Am I not your donkey that you’ve ridden until this day? Have I ever done anything like this before?” “No,” says Bilam. Suddenly, Bilam’s eyes are magically “uncovered” and he too sees the angel with the sword. Bilam bows, apologizes and offers to turn back. The angel tells him not to turn back, but he should be careful only say the words that the Divine will place in his mouth to say. So, Bilam goes on his way, and meets up with King Balak, who pleads with Bilam to curse the Israelites. But, every time Bilam opens his mouth, he pronounces blessings instead. King Balak tries again and again to get Bilam to curse, bringing him to different places on a mountain overlooking the Israelite camp, as if that would change something. But every time, it just comes out more blessings. In Bilam’s final blessing, he says, “The words of Bilam son of Beor, the words of the man with an open eye, the words of the one who hears the sayings of God, who sees the vision of Shaddai, while fallen and with uncovered eyes- “Mah tovu ohalekha Yaakov, mishkenotekha Yisrael- “How wonderful are your tents, O Jacob, your dwelling places O Israel…” -and the blessings flow on from there. So what’s going on here? Why is it that Bilam’s donkey perceives the angel before he does, and why do his eyes become “uncovered” as a result of the donkey speaking to him? And, once his eyes are uncovered, how does that allow him to “hear” the Divine voice, transforming curses into blessings? One way to grasp this passage is to understand that the donkey is your own body. There’s a tendency to take the body for granted, as if it’s just a vehicle to achieve your intentions- like a car, or a donkey that you ride on. But the spiritual potential of your body is to be a temple of Presence – a vessel for the light of your awareness. So at first, Bilam is just hitting his donkey, trying to control it. That’s the ego- selfish, angry, and entitled. But when he starts listening to what the donkey is telling him, then suddenly he can see the angel and hear it speak. Meaning, when you become present with your body, anchoring your awareness in your breathing, then you can clearly see the nature of your impulses that arise, and hear the “angels of your better nature” so to speak. So rather than simply being taken over by yoru impulses, there’s space to really see which which ones are blessings and which are curses. That’s the “uncovering of the eyes” so to speak. There’s an impulse of anger, or an urge to put someone down- you can see that clearly and not be taken over by it. Or, there’s an impulse of love, of supportiveness, of listening- that’s a blessing, and you can choose that. That’s the Yes and the No of being conscious. There’s a story that when Reb Yosef Yitzhak of Lubavitch was four years old, he asked his father, Reb Shalom Ber: “Abba, why do we have two eyes, but only one mouth and one nose?” “Do you know your Hebrew letters?” asked Reb Shalom Ber. “Yes,” replied the boy. “And what is the difference between the letter shin and the letter sin?” continued Reb Shalom. “A shin has a dot on the right side, and the sin on the left.” “Right! Now, the letter shin represents fire, and fire makes the light that we see by. The dots on the right and left are like your two eyes. “Accordingly, fire has two opposite qualities. On one hand, it can give us life by keeping us warm and cooking our food; that’s the right dot. On the other hand, it can burn us; that’s the left dot. “Similarly, there are things you should look at with your right eye, and things you should look at with your left eye. You should see others with your right eye, being warm and loving, but see candy with your left eye, not being taken over by that urge to grab at it!” So on this Shabbat Balak, the Sabbath of Seeing, may we return our awareness ever more deeply into our bodies so that can see clearly the nature of our impulses and hearthe “angels of our better nature” so that we can choose paths of blessing and peace. Good Shabbos! The Eyes of a Donkey- Parshat Balak 7/21/2016 5 Comments Once, during a monthly commute back to the Bay Area, I took an Uber from the airport to my car which was parked near our old house in Oakland. When I arrived, I got out of the Uber, unloaded my suitcases from the trunk onto the street, unlocked my dirty car that had been sitting for a month, loaded the suitcases into the car, got into the driver’s seat and reached for my cell phone to plug into the car charger. But… no cell phone! I had left it in the Uber. Immediately I looked- the Uber was half way down the street! I took off running like my pants were on fire. The car started to slow down- yes! He sees me! But then he went over a speed bump and… started accelerating again! Adrenaline pumping, I ran even faster. I yelled for him to stop. He approached a second speed bump, slowed down, and… yes! He stopped! As I reached his car, he handed me the phone out of the driver’s side window. “You’re a fast runner!” he said. “Not usually,” I replied. The body has tremendous potential, usually untapped. But in the moment of emergency, that potential can be unleashed. When I was little I remember hearing a story of a woman who lifted a car to save her child who had become trapped. But there’s another potential of the body besides its physical potential- the potential to save you by lifting the weight of ego, under which you may have become trapped. Have you ever been motivated by negativity or craving to do something that would have terrible consequences, and in that emergency your body gave you the message to stop and turn back? In this week’s reading, Balak king of Moab becomes frightened of the Israelites who are camping in a nearby valley, so he petitions the prophet/sorcerer Bilam to curse the Israelites. As Bilam rides out on his donkey to the Israelite camp, there is a strange and unique passage- one of only two instances in the Torah of talking animals (the other one being the talking serpent in the Garden of Eden). Bilam rides his donkey through a vineyard, when an angel blocks the path with sword drawn. But only the donkey can see the angel; Bilam is oblivious to it. The donkey veers off the path to avoid the sword-wielding angel, and accidentally presses Bilam’s foot into a wall. Bilam gets mad and hits donkey with a stick, at which point the animal opens her mouth and speaks: “Ma asiti l’kha- “What have I done to you that you hit me?” Bilam yells back- “Because you mocked me! If I had a sword I’d kill you right now!” Says the donkey- “Am I not your donkey that you’ve ridden until this day? Have I ever done anything like this before?” “No.” Then Bilam’s eyes are “uncovered” and he too sees the angel with the sword. Bilam bows, prostrates, apologizes, and goes up the mountain to view the Israelite camps. When Bilam opens his mouth to pronounce the curse, his mouth utters a blessing instead: “Lo hibit avein b’Ya’akov- “(The Divine) sees nothing bad in Jacob... “Mah tovu ohalekha Yaakov, mishkenotekha Yisrael- “How lovely are your tents, O Jacob, your dwelling places O Israel…” The donkey is your body- the beast you live in. You may think you want to say something, but your words will be a curse if you can’t “see the angel.” But the donkey sees it- and the donkey can talk! What is the blessing that God “wants” you to say? Your body is the gateway to this awareness, if you become present. Connect with your body, open your mouth and let the blessing come through. But, the question may arise: Isn’t the body also a hindrance to consciousness and wisdom? Isn’t your body the source of negativity and cravings? In Kabbalah, one of the symbols for wisdom is fire- as in the fire that Moses saw at the burning bush. This is the fire of Reality becoming conscious- the fire that looks through your eyes, reading these words, right now. But fire is also a symbol of destruction- of craving and negativity- as in the plague of hail and fire that rained down on the Egyptians. This is the fire of anger and craving, seducing you to satisfy its every impulse, then leaving you unsatisfied, with a trail of unwanted consequences. Both of these manifestations of fire, however, are teachers of wisdom- if only you learn to discern whether it’s the fire of “yes” or the fire of “no.” “Yes” to love, “no” to reaching- to seeing fulfillment outside yourself. “Yes” to blessing, “no” to the impulses that keep you stuck. There’s a story that when Reb Yosef Yitzhak of Lubavitch was four years old, he asked his father, Reb Shalom Ber: “Abba, why do we have two eyes, but only one mouth and one nose?” “Do you know your Hebrew letters?” asked Reb Shalom Ber. “Yes,” replied the boy. “And what is the difference between the letter shin and the letter sin?” continued Reb Shalom. “A shin has a dot on the right side, and the sin on the left.” “Right! Now, the letter shin represents fire, and fire makes the light that we see by. The dots on the right and left are like your two eyes. “Accordingly, fire has two opposite qualities. On one hand, it can give us life by keeping us warm and cooking our food; that’s the right dot. On the other hand, it can burn us; that’s the left dot. “Similarly, there are things you should look at with your right eye, and things you should look at with your left eye. You should see others with your right eye, and candy with your left eye!” On this Shabbat Balak, the Sabbath of Body-Blessing, may we keep our awareness deeply connected to our senses and our breathing, so that the fire of Presence burns brightly with wisdom and with love. May we not identify with the urgencies of craving and negativity, and know that through the power of Presence, we are totally free from their power. And may the warmth and light of that freedom deepen more and more…

The other night while I was flying back to Tucson, the flight attendant came through the cabin and asked me what I wanted to drink. “I’ll have sparkling water with lime please,” which is what I always have. “We have lime flavored sparkling water, is that okay?” No that’s not okay! That’s what I was thinking – but I said, “sure, thanks.” I’ve been getting sparkling water with lime on the plane all my life, and suddenly it was gone – and in its place, a cheaper substitute. “Lime flavor” is not the same and is not as good as a piece of real lime – on a number of levels – but business decisions like this get made all the time. So many products nowadays are worse than their predecessors. This phenomenon is sometimes called, “selling out.” “Selling out” means reducing the quality of something for the sake of monetary gain; it is an exchange of one value for another. But this doesn’t happen only in business; it is a basic ability we have to override our inner sense of what is right for the sake of something else we want. And, it’s not a bad ability to have, if used properly. For example, it’s good to exercise every day, to eat healthy food, to spend quality time with others, and so on. But what if there is an emergency – someone has a crisis and needs your help. It is good to be able to put all those things on hold temporarily and take care of the crisis. In this kind of case, “selling out” your personal health for the sake of another value – helping someone in crisis – can be a good thing. It is good to not be so attached your own needs so that you can respond to the needs of the situation. The problem is when this ability to override – to “sell out” – takes over and becomes our norm. The problem is when we completely “sell out” in the realm of personal health for the sake of a career, for example; that’s when we get into trouble. This is why it’s so important to consciously choose and create our habits. We can break them when necessary, as long as we return to them. Don’t let the exception to the rule become the new rule! Many of us are full of unconscious habits – behaviors we took on for certain reasons – that have become our norm, without ever consciously choosing them. The haftora for Parshat Hukat tells the story of Jephtah, the son of a harlot. Jephtah’s half-brothers of the same father don’t want their son-of-a-harlot half-brother to share in their inheritance, so they kick him out of the house and send him away. Now Jephtah is a great warrior, and he attracts a band of men who become his loyal companions. Years later, when the Ammonites attack Israel, the brothers come back to Jephtah and ask him to please come lead the fight against the Ammonites. “But you hated me and sent me away! Now you come back to me when you are in need?” The brothers offer him a deal: “If you come back and help us fight, then when it’s all over, we will make you our leader.” Japhteh is convinced – he “sells out” in a sense, giving up his pride and sense of justice for the sake of prestige and status. Before Japhteh goes into battle, he prays: Oh Hashem, if you make me victorious, I will sacrifice to you whatever comes out of my house first when I return home! What?? This is very strange – what does he think is going to come out of his house? Sure enough, when he returns home, his daughter runs out to greet him, and he cries out in horror as he realizes he must sacrifice his own daughter. This is such a strange story. Obviously, if he vows to sacrifice “whatever comes out of his house,” he will end up sacrificing a family member; it’s not like a goat or sheep is going to run out of his house! But if we understand the story metaphorically, it makes sense as an illustration of this “sell-out” mentality: First, Jephtah is the son of a harlot, and prostitution “sells out” the ordinary values of relationship and family for the sake of pleasure and monetary gain. Second, Jephtah agrees to help his betraying brothers fight for the sake of prestige; more selling out. Finally, he vows to sacrifice whatever comes out of his house if he wins. This is the clearest example – he is willing to sacrifice the most precious thing at a future time for the sake of gaining something else in the short run. Then, he is surprised when it leads to tragedy – just as we too can be surprised when we unconsciously make bad choices for the sake of short term, relatively unimportant goals. On the deepest level, when it comes to how we use our own minds, “selling out” tends to be the norm for most of us. Meaning: Right now, we have something so precious – the most precious thing there is in fact – we have the ability to receive this moment with love and gratitude, to know that we are an expression of the miracle of Being, in this moment. And yet, many of us unconsciously and unwittingly give up this most precious gift – for what? For mostly useless thinking. If we’re not aware of what we are doing, we can simply cover up this most precious thing with our constant stream of thoughts, just like our hand can cover our eyes and block out the entire sun. The mind has a certain illusory gravity; it says, “Pay attention to me! I have something urgently important!” But wake up to the majesty of this moment, and see: most thinking is a bogus urgency. Make it a habit to know yourself as spaciousness, as openness, rather than as busy thinking, and the miraculous becomes your norm. Yes, of course, sometimes you have to “sell out” – it’s okay – the situation will sometimes require you to get busy with your thinking, to rush around, to take care of business. Sometimes you have to put aside the most precious thing for the sake of the situation, but don’t make that the norm! When you can, come back in t’shuvah to Presence, come back to this moment, come back to the Divine as this moment – be the openness within which the fullness of this moment arises. In fact, our innate capacity to return from the trivial to the miraculous is encoded in Jephtah’s name – Yiftakh – which means, “open.” No matter how much we have “sold out,” our potential to return to openness – to know ourselves as openness – is ever-present, and we can always do it from wherever we are, in the present... More On Parshat Hukat... Rage Against Rock – Parshat Hukat