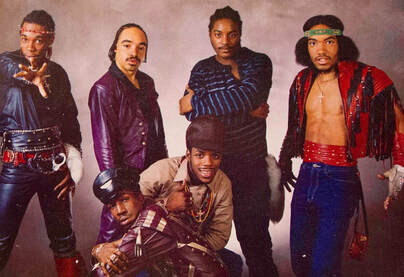

This Torah is dedicated to healing in the wake of the shooting at Chabad of Poway. May our efforts in learning and practice swiftly bring an end to hate and violence b'koarov b'yameinu, amein.  Last Sunday night, after second day Yom Tov of Pesakh, my life became complete when I took my son to see The Sugar Hill Gang and the Furious Five at the Rialto. If you don’t know, those were the first rap groups to make records and bring hip-hop into the popular culture in the late seventies. I loved them, and back in those days I too was a rapper. My child rap group, The Chilly Crew, recorded a (really bad) song (about video games) on Sugar Hill Records back in the early eighties… but that’s another story.  I got to talk to them after the show and I reminded them of The Chilly Crew. Master Gee didn’t remember me – “Man, I’m fifty-seven years old!” – but Scorpio said he remembered. I told them that I was so happy they were performing. It seems to be the nature of the hip-hop industry that rappers can’t be stars for very long. After a few years, there’s another act that takes their place. I was happy that they were going against their nature and continuing to do their thing. Flash ahead to last night, when I was getting ready to go to bed. My eyes happened to glance downward and I saw a scorpion running across the floor. I thought of Scorpio – then I flashed on the story of The Scorpion and the Fox, in which the scorpion asks the fox if he can ride on his back to cross the river. “But you will sting me,” says the fox. “Why would I do that?” replies the scorpion, “If I sting you then we will both drown.” The fox was convinced by this logic, and agreed to let the scorpion ride on its back while the fox swims across the river. When they were halfway across, the scorpion could no longer restrain itself and stung the fox. “Why did you do that?” screamed the fox. “Now we will both die!” “I couldn’t help myself,” replied the scorpion, “I guess it’s just my nature.” I promptly took a glass jar of skin cream and smashed the scorpion. I didn’t want to kill a living being, but I knew that I had to do it; scorpions in Arizona can be dangerous – it is their nature, and unlike Scorpio of the Furious Five, real scorpions don’t go against their nature. Similarly, we too have a nature – two natures, really: the nature of ego, which is our time-based identity made from thoughts and feelings, and our essential nature, which is the timeless Presence behind the ego. The question is: if we wish to go beyond the suffering of ego to the depths of peace that is our essential nature, must we kill the ego? There is a story of Rabbi David Lelov, that before he became a great rebbe himself, he was an ascetic mystic because he wished to experience the Divine Presence (which is another way of saying his essential nature). So, he fasted and engaged in other harsh practices. After six years, he still had no more perception of the Divine Presence then he had before he began, so he went another six years. Still nothing! So, he went to see Rabbi Elimelekh of Lizhenzk, whom he heard might be able to help him. When he arrived on Friday afternoon just before Shabbat, he went to the House of Prayer with the other hasidim to see the rebbe. Rabbi Elimelekh greeted everyone warmly one by one, but when he came to David, he immediately turned away and ignored him. Shocked and feeling as if he had been stabbed in the heart, David retreated back to his room at the inn. There he sat on the bed in silent disbelief about what had happened. But after some time, he began to think that the rebbe must not have noticed him. Of course, it had to be an accident! How is it even possible that a rebbe could behave that way? So, he decided to go back. When he arrived, they were just finishing the evening prayers. David made his way up to the rebbe and extended his hand in greeting. Again, the rebbe simply turned away and ignored him. His worst fear confirmed and feeling dejected, David went back to his room again and cried bitterly all night. In the morning he resolved not to visit the rebbe nor pray with the community, but to leave as soon as Shabbos was over. Hours of agony and boredom went by. Eventually it was time for Shalosh Seudes, the Third Sabbath Meal toward the end of the day as the sunlight waned. He knew this was the time when Rabbi Elimelekh would be teaching, and he suddenly felt a pull to go visit him one last time, even though he had resolved not to go back. Before he knew it, he was making his way to the House of Prayer a third time. When he arrived, he stationed himself outside a window, hoping to hear a few words of Torah without having to go inside. Then he heard the rebbe say: “Sometimes a person wishes to experience the Divine Presence, and so they fast and torture themselves for six years, and then even another six years! Then they come to me to draw down the Light for which they think they have prepared themselves. But the truth is, all that fasting is like a minute drop in an ocean, and furthermore it doesn’t rise up to the Divine at all, but instead only rises to the idol of their own ego. Such a person must give all that up and go to the very bottom of their being, and begin again from there…” When David heard these words, he almost fainted. Gasping, he made his way to the door and stood motionless at the threshold. Immediately the rebbe rose from his chair and exclaimed, “Barukh Haba! Blessed is he who comes!” The rebbe rushed over to David, embraced him, and then invited him to come sit in the chair next to his at the table. The rebbe’s son Eleazar was confused by his father’s conduct, and took him aside. “Abba, why are you being so friendly? You couldn’t stand the sight of this guy yesterday!” “Oh no, you are mistaken my son – this isn’t the same person at all! Can’t you see? This is sweet Rabbi David!” David needed Rabbi Elimelekh’s fierce grace; he needed to have that soul-poisoning “scorpion” of ego slaughtered by the rebbe. Through all those years of fasting he tried to purify himself, but that’s like the ego trying to commit suicide; it doesn’t work. It’s just more ego, only a spiritualized ego. The only way out was to have that spiritual ego smashed. If we need our egos smashed, life is usually easy to oblige; this world is full of opportunities for that. That’s one path to transcendence and freedom. But there is a second path – one not of smashing our ego, but exposing it to the light of awareness, and letting it vanish on its own. Painful insults are not the only way: רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, הֱוֵי זָהִיר בִּקְרִיאַת שְׁמַע וּבַתְּפִלָּה. וּכְשֶׁאַתָּה מִתְפַּלֵּל, אַל תַּעַשׂ תְּפִלָּתְךָ קֶבַע, אֶלָּא רַחֲמִים וְתַחֲנוּנִים לִפְנֵי הַמָּקוֹם בָּרוּךְ הוּא, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר כִּי חַנּוּן וְרַחוּם הוּא אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם וְרַב חֶסֶד וְנִחָם עַל הָרָעָה. Rabbi Shimon says: Be careful in the chanting the Sh’ma and in the Prayer. When you pray, do not make your prayer a fixed form, rather, mercy and supplication before the Place, It is Blessed, as it says (Joel 2, 13): “For (the Divine is) gracious and compassionate, slow to anger, abundant in kindness, and relentful of evil.” On one hand, Rabbi Shimon says hevei zahir – be careful or meticulous with your practice. It is something we are empowered to do; we need not rely on grace. But on the other hand, al ta’as et tefilt’kha kevah – do not make your prayer a fixed form. It doesn’t seem to make sense – it just said to be careful and disciplined about it, and now it’s saying not to make it a fixed form. Then it explains: Rather, mercy and supplication before the Place – in other words, your prayer must come from your heart, from the very “bottom of your being.” On this level, it’s not a fixed form, because each time you must find your way back to your essence, and begin again from there. Then it says: וְאַל תְּהִי רָשָׁע בִּפְנֵי עַצְמְךָ And do not be wicked to yourself. That’s the Sh’ma – the affirmation of the Oneness of Being – because it means that you too are essentially part of that Oneness. You must know that however separate you seem to feel, you can find that Reality of Oneness within your own being, because It is essentially who you are. And so, while prayer takes us into humility by pointing out our ego, the Sh’ma takes us into Divinity by pointing out our Divine nature. When you have both, you have a second path for transcendence and freedom. In this week’s Torah reading there is a hint of these two paths: one through the painful destruction of ego, and the other through sincere practice: וַיְדַבֵּ֤ר יְהוָה֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה אַחֲרֵ֣י מ֔וֹת שְׁנֵ֖י בְּנֵ֣י אַהֲרֹ֑ן בְּקָרְבָתָ֥ם לִפְנֵי־יְהוָ֖ה וַיָּמֻֽתוּ׃ The Divine spoke to Moses after the death of the two sons of Aaron when they drew close before the Divine and they died. Aaron’s two sons who are killed when they approach the Divine with their “alien fires” point to the destruction of ego, just as happened in to Rabbi David Lelov (and countless other aspirants at the hands of their teachers.) This is certainly a way, though not the preferred way. The text then proceeds to outline a preferable way: וַיֹּ֨אמֶר יְהוָ֜ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֗ה דַּבֵּר֮ אֶל־אַהֲרֹ֣ן אָחִיךָ֒ וְאַל־יָבֹ֤א בְכָל־עֵת֙ אֶל־הַקֹּ֔דֶשׁ מִבֵּ֖ית לַפָּרֹ֑כֶת אֶל־פְּנֵ֨י הַכַּפֹּ֜רֶת אֲשֶׁ֤ר עַל־הָאָרֹן֙ וְלֹ֣א יָמ֔וּת כִּ֚י בֶּֽעָנָ֔ן אֵרָאֶ֖ה עַל־הַכַּפֹּֽרֶת׃ The Divine said to Moses: Speak to Aaron your brother that he is not to come at any time into the Shrine behind the curtain, in front of the cover that is upon the ark, so that he not die; for in the cloud I appear upon the cover. Aaron is instructed not to come into the Presence b’khol eit – at any time – meaning, you can’t enter the sacred through time, through the egoic perspective which sees oneself as having achieved something over time. No amount of fasting, ritual, or learning – no amount of any accumulation that happens in time can get you there. Rather, it is only in becoming naked of time that we can enter into the Presence, because the Presence is not something separate from who we are, beneath all the accumulations of ego. That is וְתַחֲנוּנִים לִפְנֵי הַמָּקוֹם רַחֲמִים – compassion and supplication before the Place. “The Place” is a Name for the Divine; it is always the Place you are now in, the space within which this moment unfolds. Its revelation is rakhamim – compassion – in response to our takhanunim – our genuine longing; in other words, it is an act of grace. At the same time, that doesn’t mean we are passive; the grace becomes available if we have the gevurah – the strength and boundaries to be zahir – to be careful and meticulous in our practice and open ourselves again anew, day by day, hour by hour, and moment by moment. In this week of Gevurah and Akharei Mot, may we renew the boundaries of our practice while going again to the depths of our essence within the space of those boundaries… More on Akharei Mot... Separate- Parshat Akharei Mot, Kedoshim

5/3/2017 1 Comment There’s something strange about this passage. God is telling the children of Israel that they should be holy without really explaining what that means, and then it says that the reason they should be holy because God is holy- ki kadosh ani Hashem Eloheikhem. So the question is, why does one follow from the other? Why should we be holy just because God is holy, and what does holy mean anyway? The word for holy, Kadosh, actually means “separate,” but not in the ordinary sense. Normally, the word “separate” connotes distance, disconnectedness, or alienation, such as when a relationship goes sour and you lose that connection with another person. But the word kadosh actually means the opposite. In a Jewish wedding ceremony, for example, we hear these words spoken between the beloveds- “At mekudeshet li- “You are holy to me…” Meaning, your beloved becomes kadosh or “separate” not because they’re separate from you, but because they’re exclusive to you. They’re your most intimate, and therefore separate from all other relationships. So, the separateness of kadosh points not to something that’s distant, but to something that’s most central. It points not to alienation, but to the deepest connection. And just as your beloved is separate from all other relationships, so too when you become present, this moment becomes separate from all other moments, and you’re able to get some distance from the world of time- from your memories about the past and your anticipations of the future. This allows you to experience yourself not as a bundle of thoughts and feelings inhabiting a body, but as the open, radiant space of awareness within which your thoughts and feelings come and go. That’s why your presence, your awareness is by its nature kadosh- separate from the world of thought and feeling within which we tend to get trapped, yet fully and intimately connected with everything that arises in this moment. So when God says kedoshim tihyu- you should be holy- it’s telling you to do the practice of holiness by becoming present- by separating your mind from the entanglements of thought and time. How is it possible for us to get free from time? Ki kadosh ani Hashem Eloheikhem- because the holiness of Being- Hashem- is already your own inner Divinity- Eloheikhem. In other words, by practicing presence, you bring forth your own deepest nature, which is holiness. This is also hinted at in the name of Parshat Akharei Mot, which means “after the death.” In order to know your own deepest nature as shamayim mima’al, the vastness of space, you have to let go of your mind-based identity- all your stories and judgments about yourself, and that can actually feel like a kind of death. But this death has an Akhar- an afterward in which your true life, the awareness that you are, becomes liberated. So on this Shabbat Akharei Mot and Kedoshim may we come to know more deeply the holiness that is felt after the death of the false self, and may we express that holiness as love and blessing to everyone we encounter. Good Shabbos! The Flower- Parshat Akharei Mot 5/3/2016 6 Comments What does it take to set your heart free? Put another way, what is it that imprisons your heart? Once I was holding a bunch of Jewish books in my hands. My three-year-old daughter came up to me and said, “Here Abba, for you!” She was trying to give me a little flower. “One moment,” I said, “let me put these books down first.” It’s like that. The heart is imprisoned by the burden of whatever is being held. Let go of what you’re holding and the heart is open to receive. There’s a little girl offering you a flower- that flower is this moment. Put down your books and receive the gift. A friend once said to me, “I always hear that I should ‘just let go.’ But what does that mean? How do I do that?” To really know how to “let go,” we have to look at why we “hold on.” There are two main reasons the mind tends to hold on to things. First, there’s holding on to the fear about what might happen. It’s true- the future is mostly uncertain, and knowing this can create an unpleasant feeling of being out of control. Holding onto time- meaning, thinking about the future- can give you a false sense of control. There’s often the unconscious belief that if you worry about something enough, you’ll be able to control it. Of course, that’s absurd, but the mind thinks that because of its deeper fear: fear of experiencing the uncertainty itself. If you really let go of your worry about what might happen, you must confront the experience of really not knowing, of being uncertain. That can be painful, and there’s naturally resistance to pain. But, if you allow yourself to experience the pain of uncertainty, it will burn away. Don’t block the pain with a “pile of books”- that is, a pile of stories about what might be. On the other side of this pain is liberation- the expansive and simple dwelling with Being in the present. Second, there can be some negativity about what might have happened in the past. If you let go of your preoccupation with time, if you let go of whatever “happened,” you must confront the fact that the past is truly over. The deeper level of this is confronting your own mortality. Everything, eventually, will be “over.” But, let go of the past, and feel the insecurity of knowing that everything is passing. Don’t block that feeling of insecurity with a “pile of books”- with narratives about days past. Then you will see- there’s a gift being offered right now. It is precious; it is fragile- a flower offered by a little child, this precious moment. This week’s reading, Parshat Akharei Mot, begins with a warning to Aaron the Priest concerning the rites he is to perform on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement: “V’al yavo b’khol eit el hakodesh- “He shall not come at all times into the holy (sanctuary)…” We may try to reach holiness by working out the past in our minds, or by insisting on a certain future, but as it says- “V’al yavo b’khol eit… he shall not come at all times…” In other words, you cannot enter holiness through time! To enter the holy, you must leave time behind, and enter it Now. Let your grasping after the future burn, let your clinging to the past be released. As it says, continuing the description of the Yom Kippur rite- “V’lakakh et sh’nei hasirim- “He shall take two goats…” Letting go of time means letting go of past and future- one goat for the past, one for the future. The first goat, it goes on top describe, is “for Hashem”- meaning, the future is in the hands of Hashem. This goat is slaughtered and burned. Meaning: experience the burning of uncertainty and slaughter your grasping after control. The other goat is “for Azazel.” The word Azazel is composed of two words- “az” means “strength”, and “azel” means “exhausted, used up”. In other words, the “strength” of the past is “used up.” The past is gone, over, done. Let it go, or it will use you up! This goat is let go to roam free into the wilderness. The past is gone, the future is in the hands of the Divine. But those Divine hands are not separate from your hands. Set your hands free- put down the narratives- and receive the flower of this moment, as it is, and with all its creative potential for what could be… There’s a story that once Reb Yehezkel of Kozmir strolled with his young son in the Zaksi Gardens in Warsaw. His son turned to him with a question- “Abba, whenever we come here, I feel such a peace and holiness, unlike I feel anywhere else. I would expect to find it when I’m studying Torah, but instead I feel it here.” Reb Yehezkel answered- “As you know, it says in the Prophets- ‘M’lo khol ha’aretz k’vodo- the whole world is filled with the Divine Glory.’ But, sometimes we’re blocked from recognizing it.” “But Abba,” pressed his son, “Why would I be blocked from feeling the Divine Glory when I’m learning Torah? And why would I feel it so strongly in this non-religious place?” “Let me tell you a story,” answered the rebbe. “In the days before Reb Simhah Bunem of Pshischah evolved into great tzaddik, he would commute to the city of Danzig and minister to the community there, even though he lived in Lublin. “When he returned to Lublin, he would always spend the first Shabbos with his rebbe, the “Seer”- Reb Yaakov Yitzhak of Lublin. “One time when he arrived back at Lublin, he felt disconnected from the holiness he had felt while he was in Danzig. To make matters worse, the Seer wouldn’t give him the usual greeting of “Shalom,” and in fact behaved rather coldly to Reb Simha. “Figuring this was just a mistake, he returned to the Seer some hours later, hoping to get a blast of the rebbe’s spiritual juice, but again the Seer just ignored him. He left feeling dry and sad that his rebbe had rejected him. “Then, a certain Talmudic teaching came to his mind: that a person beset with unexpected tribulations should scrutinize their actions. “So, he mentally scrutinized every detail of his conduct in Danzig, but he couldn’t recall anything he had done wrong. If anything, he noted with satisfaction that this visit was definitely of the kind that he liked to nickname ‘a good Danzig,’ for he had brought down such holy ecstasy in the prayers and chanting. “But then he remembered the rest of the teaching. It goes on to say- ‘Pishpeish v’lo matza, yitleh b’vitul Torah- ‘If he sought and did not find, let him ascribe it to the diminishing (bitul) of Torah.’ “Meaning, that his suffering must be caused by having not studied enough. “Taking this advice to heart, Reb Simhah decided to start studying right then and there. Opening his Talmud, he sat down and studied earnestly all that day and night. “Suddenly, a novel light on the Talmudic teaching dawned on him. He turned the words over in his mind once more: ‘Pishpeish v’lo matza, yitleh b’vitul Torah.’ “He began to think that perhaps what the sages really meant by their advice was not that he didn’t study enough, but that he wasn’t ‘diminished’ (bitul) by his studying. Rather than humbling himself with Torah, all that book knowledge was simply building up his own ego, and blocking his connection with the Presence. As soon as he realized this, he ‘let go’ of the books- he let go of being a great scholar, and the Presence that he longed for returned. “Later that evening, the Seer greeted him warmly: ‘Danzig, as you know, is not such a religious place, yet the Divine Presence is everywhere, as it says- the whole world is filled with Its Glory. If, while you were there, the Divine Presence rested upon you, this was no great feat accomplished by your extensive learning- it was because in your ecstasy, you opened to what is always already here.’” On this Shabbos Akharei Mot, the “Sabbath After the Death,” may all that we hold out of pride drop away. May all that we hold out of fear drop away. May all that we hold in an attempt to control drop away… and may we live in this holiness that is always already here.

0 Comments

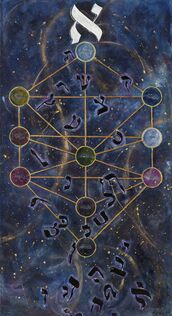

A Lithuanian man once came to Rabbi Nahum of Tchernobil and complained that he had no money to marry off his daughter. The rebbe happened to have fifty gulden put aside for another purpose, but he immediately gave all of it to the man. He then went and fetched his silk robe. “Now you will be able to dress well for this joyous occasion!” the rebbe said and offered the man the robe. The man took everything, went straight to an inn, and began drinking vodka. A few hours later, some of the Hasidim went to the inn and found him lying on a bunch, completely drunk. Flabbergasted, they took the rest of the money and the silk robe away from him and brought it all back to Rabbi Nahum. “That Litvak betrayed you, Master!” “What is this?” cried the rebbe, “I just caught hold of the tail end of the Divine quality of unconditional kindness, and you want to snatch it from my hands? Take it all back to him at once!” This week begins what is known as the sefirat ha’omer period between the festivals of Passover and Shavuot. Each of these seven weeks represents a sefirah, or Divine emanation, which correspond to practical middot, or “Divine Qualities” that we can practice and embody. These Qualities are really different ways that Presence expresses Itself in different situations. There are two main ways of working with the Qualities: One way is to think about them, study them, and do exercises and practices to internalize them. Most spiritual practice is like this – you step out of the flow of life and into the laboratory of meditation, prayer, ritual or study. The practice of tzeddaka (giving charity) is like this; it’s an artificial way of making sure that your resources are expressing generosity. By using the word “artificial” I don’t mean to imply anything negative. “Artificial” just means something separate from the spontaneous flow of life, something that embodies a specific intention, like any art. But there’s another way of working with the middot that is more primary, and that’s the spontaneous expression of the Divine Qualities in the flow of life. When Reb Nahum gave the money and robe to the drunkard, it wasn’t because he had set aside money for the purpose of charity; it wasn’t preconceived. Rather, it flowed from the heart of one who is free, one who is not controlled by the ordinary impulses of stinginess or selfishness or even self-responsibility. We can all do this at any moment, but it is difficult of course because the thinking mind tends to give importance to its own thoughts and conceptions of the past and future, while unconsciously “passing over” the supreme opportunity of the present. To overcome unconsciousness and be awake to the only opportunity that really matters, realize: the time to express the Divine Qualities is now. Bring you awareness to the fulness of whatever is present, and know that this moment is the altar upon which we bring our offering. כִּֽי־קָר֥וֹב אֵלֶ֛יךָ הַדָּבָ֖ר מְאֹ֑ד – Ki karov elekha hadavar me’od- for this thing is very close to you!” (Deuteronomy 30:14) Practice being the lovingkindness with whatever is present. There is always a way to do it; whether it’s expressing kindness to another person or simply giving attention to your own feelings as an act of kindness. When we become present, Hesed is a natural dimension of the Presence that we already are… if we can but remember to access it. (Artwork from the collection of Jim Kamillos) More On Hesed... 4/16/17 So let’s explore Hesed, or Lovingkindness, by looking at the root mitzvah for Hesed. (In case you don’t know, the word mitzvah means commandment, and it comes from the traditional idea that God gave mitzvot, or commandments to the Jewish people through the prophet Moses about 35,00 years ago. Now you may or not believe in that literally, but the point is that the Jewish practices known as mitzvot are very ancient and they’re a way to connect the work of your spiritual awakening to the tremendous richness that flows from the Jewish lineage.) So what is the root mitzvah of Hesed? It’s the mitzvah known as ahavat Hashem- love of God. The text of this mitzvah is traditionally chanted four times a day as part of the Sh’ma and comes from Deuteronomy, or Devarim, chapter 6 verse 5. It says, Ve’ahavtah et Hashem Elohekha b’khol levavkha uv’khol nafsh’kha uv’khol meodekha- Love Hashem your God with all your heart, all your soul and all your might. Now this mitzvah is strange for a number of reasons. First of all, how can you intentionally love something? Isn’t love a feeling that either arises on its own or it doesn’t? Can you actually decide to love something or someone, or does your heart simply feel however it feels? Second of all, if we dig a little deeper into the language, we see that the Name of God is composed of the letters Yod, Heh, and Vav and Heh, which come from the verb “to be,” so the Name of God really means Existence or Reality, as I’ve also mentioned in the IJM materials. Now if you experience something that you already love, such as closeness with a person you love or you hear some music that you love, or taste some food that you love, then it’s relatively easy to elevate that experience into ahavat Hashem through gratitude. You simply give thanks for the gift that you’re experiencing, and that gratitude opens you to an even deeper pleasure of connection. However, ahavat Hashem through gratitude is incomplete by itself. That’s because by definition, Existence or Reality includes everything that exists- everything that’s real- not just the things you love. So how does it make sense to love everything that is? Isn’t the very experience of love based on the fact that you love some things and not other things? How can you love something that’s evil for example, or how can you love being sick, or being in pain, and so on? It seems that the very reality of love is dualistic- we love somethings and hate other things. So how can you possibly love God, how can you do the mitzvah of ahavat Hashem if Hashem includes everything, even the most hateful things. So let’s explore this a bit. Imagine that you are a sculptor who works with clay. So for you, clay is the most wonderful thing because it’s the medium of your craft. Your whole life is devoted to working with clay. You LOVE clay. But, you’re also very opinionated about what makes a good sculpture and what makes a bad sculpture, and because you’re so serious about your art, nothing is more disturbing to you than a terrible sculpture. Along comes one of your new students who hasn’t learned much yet, and they eagerly show you their latest work, which happens to be a terrible sculpture in your opinion. So what do you do? Do you whack your student in the head and vow to never touch clay again because of the ugly thing your student made? That would be really immature and kind of crazy, right? Hopefully your hatred of the sculpture would instead motivate you to help your student improve. If you’re a mature person, then you can love your student even if you hate this particular sculpture they made. You can also, of course, continue loving clay even though the bad sculpture was made out of clay, because clay in general and the bad sculpture in particular exist on two totally different levels; you can hate the sculpture and yet love the clay that it’s made from, and also love the person who made it. It’s all just a question of where you put your energy and attention. The analogy here is that the clay represents Being or Existence. You can love God, meaning Being or Existence, while still disliking some particular experiences. But, you may ask, this analogy takes for granted that you love clay. What about the case of someone who doesn’t love clay? In other words, we’re still left with the problem- how do you command ahavat Hashem? With clay it makes more sense. You’re a sculptor, you love clay, though you may not like a particular sculpture. You’re a musician, you love your instrument, though you may not like every piece of music that can be played on it. But what does it mean to love Existence or Being, and how can you possibly practice that? Let’s look at what happens when you’re craving something, and then you get what you’re craving. Take food for example. You feel the pain of hunger, the desire to eat something, and then you eat it and feel satisfaction. But there’s something else going on that you might not be aware of unless you’re really paying attention, and that is the sense of incompleteness that’s caused not by the hunger, but by the mental and emotional fixation on the object of your desire. It’s not just that you’re hungry, it’s that there’s a basic dis-ease with the present moment, and a psychological “reaching” for a future moment when you imagine that you’ll be satisfied. Then, when you finally get what you were craving, not only is there a satisfaction with the experience of the food, there’s also hopefully a relaxing into present moment reality while you enjoy the food, and a dropping away of that dis-ease of wanting. And that simple connection and dropping away of dis-ease is itself very pleasurable, and naturally lovable, even more so perhaps than the food. Now everyone experiences this at least to some degree, but rarely to people realize that what’s going on. Instead, people just assume that all the pleasure comes from the food or whatever particular gratification they’re experiencing. But the truth is, the deeper pleasure comes not from the food, though food is certainly a wonderful thing, but from the letting go of wanting and instead connecting deeply with the present. That’s why we have practices like fasting, for example, or giving up bread on Pesakh. Normally when we feel a craving, the heart tends to run after what we want and we lose connection with the present. But if you let yourself feel the craving on purpose, returning your attention to your heart again and again so that it doesn’t carry you away, then you can learn to open your heart and drop into the wholeness and bliss of the Present without needing to satisfy whatever urge you’re feeling. In that way, you get to experience Ahavat Hashem- love of God- meaning love of Being or Existence or Reality Itself, because your connection to the Reality of the present is by its nature very pleasurable, healing and liberating. There’s a hint of this in the Torah reading Parshat Sh’mini. It opens, “Vay’hi bayom hashmini kara mosheh- It was on the eighth day that Moses called out." Moses then gives instructions to the Israelites for the offerings they should bring in order for them to have a vision of the Divine. It then goes on in great detail about the animals and grains and oils they burned as fire offerings. At the end of this litany it says, “… vayeyra kh’vod Hashem el kol ha’am- the Divine Glory appeared to all the people.” Why? When you experience satisfaction such as eating delicious food, you can elevate that experience through gratitude- through realizing that your food is literally a gift from God, emerging from the field of Being. But if you want to experience ahavat Hashem- the love of God that’s there even when you’re not feeling satisfied, you have to differentiate the pleasure that comes from Presence from the pleasure that comes from gratification, and you can do that through sacrifice- through purposely giving something up. Then, just as the Divine Glory appeared to the Israelites, so you too will perceive the deep satisfaction and bliss of connecting with Reality as it is, beyond all those temporary and finite pleasures, wonderful as they might be. And when you do that, a much deeper gratitude can emerge- gratitude not only for the particular blessings we experience, but for the constant opportunity we have to practice Presence and connect with the completeness and peace of this moment. This is also hinted at in the opening verse, “Vay’hi bayom hashmini- It was on the eighth day…” Y’hi is a form of the verb “to be.” Bayom means “on the day” but it can also mean “in today”- meaning, in the Present. Hashmini means, “the eighth.” The number eight on its side is a symbol for infinity. So the idea here is that you connect with the Eternal- hashmini- through Being- y’hi- in the Present- bayom. Now all of this may seem every complex. But at its root, it comes down to returning your attention to your heart, again and again. When you crave something, it’s as if your heart is running after what it wants, disconnecting from this moment. But when you return your attention to your heart, you open to reality as it is, and all that heart energy that normally wants to run after things opens into that deeper bliss of Being... Divine Remembrance-Hesed Week 4/3/18 The matzah that is traditionally eaten this week represents two qualities: immediacy and intimacy.

Immediacy, because since there was a hasty departure from Egypt, the dough had no time to rise. This hints at the immediate accessibility of Reality/Divinity; there's no process to come to this moment. As soon as you intend it, you do it, now. Intimacy, because the rising of dough is the separation of the substance of the dough away from itself, caused by the bubbles from the yeast. This is a wonderful metaphor for what happens in consciousness: we identify with certain aspects of our experience, such as thoughts and feelings, and objectify other aspects of our experience, such as things happening in our environment. But everything in experience is, by definition, made of consciousness. So when we become present, the "dough" of consciousness is permitted to collapse into itself, like the thin matzah. This moment is experienced simply as it is, without separation. These two aspects, immediacy and intimacy, also correspond to the two "wings" of prayer – Yirah and Ahavah, Fear and Love. Yirah is not the anxious fear of worry and anxiety, it is simply a healthy respect for danger. In this sense, Yirah means being careful with your own mind, being watchful, guarding yourself against too much meandering of thought. Ahavah, Love, means being open and giving of yourself to the fullness of Being as it manifests now, in an open hearted, even passionate way. It is regarding the immediacy of Reality as the Face of the Divine, and remembering the Divine constantly, similarly to how you might constantly think of a person you're infatuated with. Yirah and Ahavah also correspond to the dual practice of Shamor V'Zakhor, Guarding and Remembering, alluded to in the Shabbat hymn, L'kha Dodi. Shamor, "guarding," means guarding your own mind. Zakhor, "remembering," means remembering that the Divine is present as whatever is living in your experience, right now. This practice of Zakhor, remembering the Divine, is expressed in the Sufi practice of chanting Divine Names, known as zikr. Although this is a sufi practice, the son of Moses Maimonides, Avraham Maimonides, claimed that the Sufis had preserved the ancient practices of Israel in their zikr, and that the Jews could recover their ancient lineage of chanting Divine Names by re-adopting it from the Sufis! There's a hint of this in the verse (Exodus 21:29): בְּכָל־הַמָּקוֹם֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר אַזְכִּ֣יר אֶת־שְׁמִ֔י אָב֥וֹא אֵלֶ֖יךָ וּבֵֽרַכְתִּֽיךָ In all places that I cause My Name to be remembered – azkir et Sh'mi – I will come to you and bless you. The understanding of azkir, "I will cause to be remembered," is not merely a mental remembering, but remembering through chanting the Name. That's why many English translations of this verse translate azkir as, "I will cause to be spoken." There's a story about Rabbi Israel, the Maggid of Koznitz, that he used to visit the town of Apt every year in order to visit the grave of his father. One time while he was visiting, the townspeople came and asked if he would preach in the synagogue on Shabbos as he did last time. "Why would I do that?" he replied, "There's no evidence that the preaching I did last time did any good." The townspeople were greatly upset, and gathered around his inn to try and persuade him. Finally, a craftsman went in and knocked at his door. When the Maggid opened the door, and the craftsman said, "You claim that your preaching last year did no good, but that's not true. I heard you teach that a person should always practice the verse from Psalm `16, שִׁוִּיתִי יְהוָה לְנֶגְדִּי תָמִיד – Shviti Hashem L'negdi Tamid – I place the Divine Name before me constantly. Since then, I always keep the Divine Name in my mind, remembering that the Divine is always present in every moment." "In that case," replied the Maggid, "I will come and preach."

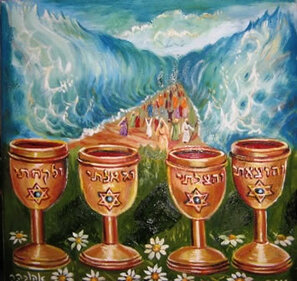

Recently someone told me that he was angry at someone. And, not only was he angry, but he likes being angry; he had no desire to “let go” or “get over it.” Then, a few days later, another person told me almost the same thing about someone else, but with the addition: “I will never forgive.” There’s an idea that the festivals contain certain transformational potentials, and that as we enter their seasons, the barriers that we need to transcend start coming to the surface. And certainly, anger and non-forgiveness are ways that we can get stuck in Mitzrayim, in narrow identification with feelings of woundedness, of being a victim. But getting free doesn’t have to mean a denial or pushing away of our true feelings; rather, it is precisely our true feelings that are the means to liberation. They are the gravity of unconsciousness that forces us to either wake up or get pulled in. Without them, there can be no liberation; that’s the sacred role of Egypt and Pharaoh. According to the structure of the Passover seder, this process of liberation has four basic stages, corresponding to the four cups of wine. The Jerusalem Talmud (10a) asks, “Why do we have four cups of wine? Rabbi Yochanan said in the name of Rabbi Benayah, this refers to the four stages of redemption.” לָכֵ֞ן אֱמֹ֥ר לִבְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֘ל אֲנִ֣י יְהוָה֒ וְהוֹצֵאתִ֣י אֶתְכֶ֗ם מִתַּ֙חַת֙ סִבְלֹ֣ת מִצְרַ֔יִם וְהִצַּלְתִּ֥י אֶתְכֶ֖ם מֵעֲבֹדָתָ֑ם וְגָאַלְתִּ֤י אֶתְכֶם֙ בִּזְר֣וֹעַ נְטוּיָ֔ה וּבִשְׁפָטִ֖ים גְּדֹלִֽים׃ וְלָקַחְתִּ֨י אֶתְכֶ֥ם לִי֙ לְעָ֔ם וְהָיִ֥יתִי לָכֶ֖ם לֵֽאלֹהִ֑ים וִֽידַעְתֶּ֗ם כִּ֣י אֲנִ֤י יְהוָה֙ אֱלֹ֣הֵיכֶ֔ם הַמּוֹצִ֣יא אֶתְכֶ֔ם מִתַּ֖חַת סִבְל֥וֹת מִצְרָֽיִם׃ Therefore, say to the children of Israel: “I am Reality. I will bring you out from under the burdens of Egypt, and I will rescue you from their work. I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and through great judgments. I will take you to Me as a people, and I will be for you as a God. And you shall know that it is I, Existence Itself, your own Divinity, Who brought you out from under the burdens of Egypt…” (Exodus 6:6 – 7) Hotzeiti – I will bring you out: There is a difference between the experience of liberation and the reality of liberation. Experience is always in motion; the degree to which we experience freedom changes from moment to moment. The reality of our freedom, on the other hand, is absolute; it is our task to recognize it and live it, regardless of our experience in the moment. The experience we’re having right now arises within our field of awareness; awareness is not trapped or compelled by it in any way. I am Reality – I will bring you out. The simple recognition of our own being as the vast and formless field of awareness within which this present experience is now unfolding brings us out from the illusion of being stuck, into the reality of our inherent freedom. Hitzalti – I will rescue you: Once we recognize our freedom in the present, there is always the possibility that we will forget and again get drawn back into the dream of bondage. After all, the illusion is so formidable! The Egyptian army is behind us, the sea is in front of us – what shall we do? Our recognition must become commitment; we must remember to return ourselves to this recognition again and again in the face of the seductive and encroaching tides of experience. Ga’alti – I will redeem you: When we come to the recognition of and commitment to our absolute freedom in the present, there can be a tendency to deny our past, which only creates a more subtle form of bondage. But when we embrace our past, when we recognize that ALL of our past experience, no matter how discordant or even evil, has brought us to this present moment of wakefulness, there can be redemption. There is no doubt – slavery and oppression are wrong. They are to be opposed. But, they are part of our sacred history, and through the telling, they have a sacred role. Gam zeh l’tovah – this too is for the good. This is not to whitewash or deny our pain; it is to embrace the supreme potential given to us by that pain. Lakakhti – I will take you: It is true, there is nothing more vital for our own wellbeing then liberation. Anger and resentment can be sweet in a strange way, but they are nothing compared to freedom. And yet, it may take many years of bondage and many plagues to convince us that freedom is preferable. We cling to our bondage as if our life depended on it! And in a way, it does, because the price of freedom is our very identity; freedom changes who we think we are. At this stage, we give up fascination with our own story, with our own process, and meet the Divine at Sinai to answer Its call. Freedom is not merely for ourselves; it is the liberation of Reality Itself, waking up to Itself… More on Passover...  Kadesh, Karpas 3/27/2018 It is told about Rabbi Elimelekh of Lizhensk that when he chanted the Kiddush, he would repeatedly look at his watch in order to keep himself connected to the world of time, otherwise he might dissolve into the Eternal completely. In spiritual awakening there is a kind of balance that must be struck between the "world of time" – a.k.a the thinking mind, and the "Eternal World" – a.k.a. the space of awareness within which the thinking mind functions. While all the holy days and Shabbat are designed to help you dip more deeply into the Eternal World, the ritual of kiddush – the sanctification of the holy day with wine – points most strongly to this Eternal dimension of experience. As it says in the Friday night Kiddush as well as all the festivals, "Zekher L'tziyat Mitzrayim – Remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt." It is a "remembrance" because the condition for freedom is already fulfilled; you just have to remember it. You are already free as Presence, as the open space of awareness within which experience arises. And yet, even though you always already are freedom as awareness, embodying this truth in life is challenging; it requires constant effort. The Ishbitzer Rebbe pointed out that this is symbolized by the Karpas, the ritual vegetable eaten at the seder, because vegetables have to be planted again and again year after year. Whatever state was achieved yesterday, it is over today; we must constantly apply our awareness to overcome the forces of bondage within, day after day. Which brings us to Urkhatz, the washing of hands that happens between Kadesh and Karpas. Wash yourself of yesterday's conditioning; today we must start again...  Re-Membering for Passover 4/3/2017 What is spiritual bondage? When the Torah describes the beginning of the Israelite’s bondage in Egypt, is says, “Vaya’avidu Mitzrayim et b’nai Yisrael b’farekh- Egypt enslaved the children of Israel with farekh- with crushing servitude.” Now within this verse are three hints about the nature of spiritual bondage. The first hint is in the word farekh, which means crushing labor. Now the root of farekh means to break apart or fracture, hence its usage to describe “crushing” labor. The obvious hint here is that spiritual bondage is unpleasant- it involves suffering. But on a deeper level, it hints that there is some kind of breaking or fracturing happening, and that’s the fracturing of Reality Itself as it appears in your consciousness. Consider- in this moment, everything is as it is, and your consciousness is meeting whatever is appearing- your sensations, your feelings, your perception of what’s around you, whatever thoughts arise, and so on. As long as consciousness simply meets what is, there’s a wholeness to Everything. But when something unpleasant arises, whether external or internal it doesn’t matter, because all experience arises within the one space of consciousness, there’s a tendency for consciousness to contract into resistance, in the form of thoughts, feelings, or even words and actions- “dang farnet- what the??”- that’s resistance- that’s the farekh- the tearing apart of Reality, because now there’s me over here, resisting that over there, even if the “over there” is on my own mind. This move from Wholeness to an opposing position implies a kind of contraction, because now rather than simply being the space of awareness within which all experience happens, you become a finite entity, resisting something within your experience. This brings us to the second hint in this verse, the word Mitzrayim. Mitzrayin means Egypt, but it comes from the root tzar which means “narrow,” probably because Egypt was built along the Nile. But metaphorically, it hints that to be in mitzrayim is to be in a narrow state; the native and full spaciousness of your consciousness gets contracted into a fixed point of view- the narrow “me” called “ego.” And what’s the basic activity of ego? Ego tries to control things. That’s because ego feels disconnected from the fullness of its experience. That’s the basic hallmark of ego- that feeling of incompleteness, and with it, the need to change things in order to be okay. That egoic feeling of incompleteness comes from the contraction into a mitzrayim state that happens spontaneously in reaction to farekh- suffering that breaks apart the wholeness of your experience. And this brings us to the third hint in the verse, vaya’avidu, which means “enslaved.” The arising of suffering, represented by farekh, which causes the contraction into the ego, represented by Mitzrayim is obviously not something we consciously choose; it seems to just happen to us. Vaya’avidu Mitzrayim et b’nai Yisrael- that contraction just seems to grab you and enslave you against your will. And yet, on a deeper level, ya’avidu is related to the word Avodah, which means work or service not in the negative sense of slavery, but in the positive sense of prayer, or spiritual practice- which is an act of love and devotion. The hint here is that the experience of suffering and the spiritual bondage that comes from it has a purpose, and that is to be transformed into avodah, into a path of liberation. Because it’s only from experiencing and getting caught in all kinds of spiritual bondage, and then finding your way out of bondage, that you can really mature and evolve. A baby in the womb is already whole and one with all being, but it’s not liberated, because there’s no appreciation of the Wholeness. In order to know liberation, you have to first taste bondage. The danger, of course, is that the experience of bondage, however that manifests for you, seduces you into a negative attitude and you become resigned to your stuck-ness. That’s why the Torah says, “l’maan tizkor et yom tzeitkha me’eretz mitzrayim kol y’mei khayiekha- that you remember your going out from Egypt all the days of your life.” This verse, which also appears near the beginning of the seder, urges us to constantly remember that our basic nature is freedom, reminding ourselves every day, and even every night as the words of the seder say, “Kol y’mei khayiekha, l’havi haleilot- all the days of your life means, the nights also.” And what’s the every day and night practice for remembering the going out of Egypt? It’s the chanting of the Sh’ma, because the Sh’ma reminds us, Hashem Eloheinu- Hashem- All existence- meaning everything that arises in your experience- is Eloheinu- your own inner divinity, meaning your awareness. Then it says, Hashem Ekhad- Existence, or Reality is One. Again and again you may get pulled into farekh- that involuntary suffering in which we contract into the egoic mitzrayim state, but if you remember ekhad- the oneness of Being, you can find your way back into harmony with what is through the verse that follows: ve’ahavtah et Hashem Elohekha- Love Hashem your Divinity, that’s the Hesed- the lovingkindness of offering your awareness as a gift to this moment just as it is, even if it feels like suffering, that’s the first part of meditation, b’khol l’vavkha uvkhol nafshekha uv’khol me’odekha- with all your heart and soul and might- that’s the Gevurah, the strength, of grounding and sustaining your awareness in your body- that’s the second part of meditation, and of course, Sh’ma Yisrael- Listen, be aware, and know yourself as the awareness- spacious, free and borderless- that’s the third part of meditation.  The Perfect Passover 4/20/2016 3 Comments One Passover, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev led the first night seder so perfectly, that every word and every ritual glowed with all the holiness of its mystical significance. In the dawn, after the celebration, Levi Yitzhak sat in his room, joyful and proud that he had performed such an perfect seder. But all of a sudden, a Voice from above spoke to him: “More pleasing to me than your seder is that of Hayim the water-carrier.” “Hayim the water-carrier?” wondered Levi Yitzhak, “Who’s that?” He summoned all his disciples together, and asked if anyone had heard of Hayim the water-carrier. Nobody had. So, at the tzaddik’s bidding, some of the disciples set off in search of him. They asked around for many hours before they were led to a poor neighborhood outside the city. There, they were shown a little house that was falling apart. They knocked on the door. A woman came out and asked what they wanted. When they told her, she was amazed. “Yes,” she said, “Hayim the water carrier is my husband, but he can’t go with you, because he drank a lot yesterday and he’s sleeping it off now. If you wake him, you’ll see he won’t even be able to move.” “It’s the rabbi’s orders!” answered the disciples. They barged in and shook him from his sleep. He only blinked at them and couldn’t understand what they wanted. Then he rolled over and tried to go on sleeping. So they grabbed him, dragged him from his bed, and carried him on their shoulders to the tzaddik'shouse. There they sat him down, bewildered, before Levi Yitzhak. The rabbi leaned toward him and said- “Reb Hayim, dear heart, what kavanah, what mystic intention was in your mind when you gathered the hameitz- the leavened foods- to burn in preparation for the seder?” The water carrier looked at him dully, shook his head and replied, “Master, I just looked into every corner and gathered it together.” The astonished tzaddik continued questioning him- “And what yihudim- what holy unifications did you contemplate when you burned it?” The man pondered, looked distressed, and said hesitatingly, “Master, I forgot to burn it, and now I remember- it’s all still lying on the shelf.” When Rabbi Levi Yitzhak heard this, he grew more and more uncertain, but he continued asking- “And tell me Reb Hayim, how did you celebrate the seder?” Then something seemed to quicken in his eyes and limbs, and he replied in humble tones- “Rabbi, I shall tell you the truth. You see, I had always heard that it’s forbidden to drink brandy on all eight days of the festival, and so yesterday morning I drank enough to last me eight days. Then I got tired and fell asleep. “When my wife woke me in the evening, she said, ‘why don’t you celebrate the seder like all the other Jews?’ “I said, ‘What do you want from me? I’m an ignorant man and my father was an ignorant man. I don’t know how to read, and I don’t know what to do, or what not to do.’ “My wife answered, ‘You must know some little song or something!’ “I thought for a moment, and then a melody and words came to me that I had heard as a child. I sang- “Mah nishtana halaila hazeh mikol haleilot- Why is this night different from all other nights? “I thought, 'why is this night different?' “Then, something strange happened. It was as if I awoke from a dream, and everything was suddenly more real, more present. It was as if the night itself woke up all around me… “Then I looked and saw the table before me, and the cloth gleamed like the sun, and on it were platters of matzot, eggs, and other dishes, with bottles of red wine. So we ate of the matzot and eggs and drank of the wine. “I was overcome with joy. I lifted my cup to the heavens and said, 'Oh Hashem- I drink to you!' “Then we sang and rejoiced in the nishtana- the specialness- of that moment… then I got tired and fell asleep.” So my friends- before you fall asleep! Why is this moment different? On this Shabbat Pesakh, the Sabbath of Passing, may we awaken to know that everything is passing, savoring the unique specialness of this moment. Let the unfolding of Reality become what it will, letting go of whatever it was, and breathing the intention of peace and love and awareness into every thought, every word, every act. Let’s go forth, again, out of mitzrayim- out of constriction- and into the mystery of the Presence as the present. This moment is truly different from all other moments, and always is…

רַבִּי יַעֲקֹב אוֹמֵר, הָעוֹלָם הַזֶּה דּוֹמֶה לִפְרוֹזְדוֹר בִּפְנֵי הָעוֹלָם הַבָּא. הַתְקֵן עַצְמְךָ בַפְּרוֹזְדוֹר כְּדֵי שֶׁתִּכָּנֵס לַטְּרַקְלִי Rabbi Yaakov says: This world is like a waiting room before the World to Come. Fix yourself in the waiting room so you may enter the banquet hall! (Pirkei Avot 4:24) One of the most basic dualities on the spiritual path is the “before” and “after” of waking up. Both the “banquet hall” and “the World to Come” are metaphors for this aim of the path: the complete “fixing” of our sense of incompleteness and arriving into wholeness. Before that, we may get glimpses of the Wholeness – the door cracks open and for a moment we can see… Once, a disciple complained to his rebbe that when in the rebbe’s presence, Divine Reality is palpable and he has peace. But as soon as he leaves the rebbe’s presence, it all vanishes and his suffering returns. “This is like a person who gropes about in the dark forest,” answered the rebbe, “and someone comes along with a lantern and walks with him for a while. For a time, he can see where he is going. But eventually, the guy with the lantern goes his own way, and the person is left alone again in the dark. This is why it’s so important to carry your own lantern!” When we get that glimpse – either through a rebbe or any other means – it should remind us to work on igniting our own flame. Hat’kein atzm’kha – we have to “fix” ourselves in the “waiting room.” How do we do that? Take the time to simply “wait” – be aware of the inner darkness – that is meditation. The awareness is itself the Light – it is your own inner Light. But if you spend all your time in thought and activity, you may not notice… וְאִם־בַּהֶרֶת֩ לְבָנָ֨ה הִ֜וא בְּע֣וֹר בְּשָׂר֗וֹ ... וְהִסְגִּ֧יר הַכֹּהֵ֛ן אֶת־הַנֶּ֖גַע שִׁבְעַ֥ת יָמִֽים׃ And if it is a white discoloration on the skin of his body ... the priest shall isolate the affected person for seven days… (Leviticus 13:4) This week’s parsha talks about tzara’at – an affliction of the skin that renders a person tamei – ritually unfit to enter the Sanctuary. The affected person has to be quarantined for a period to become purified. The skin is a metaphor – it is the physical boundary of self, representing that inner sense of oneself as separate, called ego. The “affliction” hints at the ego’s feeling of incompleteness, of being disconnected, of having “not yet arrived.” The remedy: withdraw from the world of time, into solitude with the feeling. Be the Light, illuminating the darkness in solitude for “seven days” – meaning, until you reach Shabbat! Shabbat is that arriving into the spaciousness that is your deepest essence – the field of awareness itself, within which this moment arises. So next time you find yourself in a waiting room, or waiting in line, remember the opportunity for illumination that comes as a hidden gift in those moments... Good Shabbos! More on Parshat Tazria... Cage Free – Omer and Tazria – Metzorah