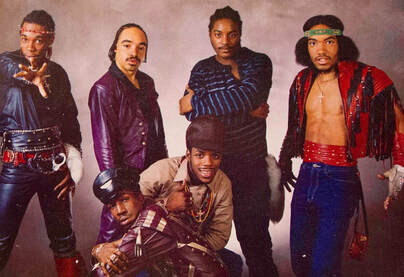

This Torah is dedicated to healing in the wake of the shooting at Chabad of Poway. May our efforts in learning and practice swiftly bring an end to hate and violence b'koarov b'yameinu, amein.  Last Sunday night, after second day Yom Tov of Pesakh, my life became complete when I took my son to see The Sugar Hill Gang and the Furious Five at the Rialto. If you don’t know, those were the first rap groups to make records and bring hip-hop into the popular culture in the late seventies. I loved them, and back in those days I too was a rapper. My child rap group, The Chilly Crew, recorded a (really bad) song (about video games) on Sugar Hill Records back in the early eighties… but that’s another story.  I got to talk to them after the show and I reminded them of The Chilly Crew. Master Gee didn’t remember me – “Man, I’m fifty-seven years old!” – but Scorpio said he remembered. I told them that I was so happy they were performing. It seems to be the nature of the hip-hop industry that rappers can’t be stars for very long. After a few years, there’s another act that takes their place. I was happy that they were going against their nature and continuing to do their thing. Flash ahead to last night, when I was getting ready to go to bed. My eyes happened to glance downward and I saw a scorpion running across the floor. I thought of Scorpio – then I flashed on the story of The Scorpion and the Fox, in which the scorpion asks the fox if he can ride on his back to cross the river. “But you will sting me,” says the fox. “Why would I do that?” replies the scorpion, “If I sting you then we will both drown.” The fox was convinced by this logic, and agreed to let the scorpion ride on its back while the fox swims across the river. When they were halfway across, the scorpion could no longer restrain itself and stung the fox. “Why did you do that?” screamed the fox. “Now we will both die!” “I couldn’t help myself,” replied the scorpion, “I guess it’s just my nature.” I promptly took a glass jar of skin cream and smashed the scorpion. I didn’t want to kill a living being, but I knew that I had to do it; scorpions in Arizona can be dangerous – it is their nature, and unlike Scorpio of the Furious Five, real scorpions don’t go against their nature. Similarly, we too have a nature – two natures, really: the nature of ego, which is our time-based identity made from thoughts and feelings, and our essential nature, which is the timeless Presence behind the ego. The question is: if we wish to go beyond the suffering of ego to the depths of peace that is our essential nature, must we kill the ego? There is a story of Rabbi David Lelov, that before he became a great rebbe himself, he was an ascetic mystic because he wished to experience the Divine Presence (which is another way of saying his essential nature). So, he fasted and engaged in other harsh practices. After six years, he still had no more perception of the Divine Presence then he had before he began, so he went another six years. Still nothing! So, he went to see Rabbi Elimelekh of Lizhenzk, whom he heard might be able to help him. When he arrived on Friday afternoon just before Shabbat, he went to the House of Prayer with the other hasidim to see the rebbe. Rabbi Elimelekh greeted everyone warmly one by one, but when he came to David, he immediately turned away and ignored him. Shocked and feeling as if he had been stabbed in the heart, David retreated back to his room at the inn. There he sat on the bed in silent disbelief about what had happened. But after some time, he began to think that the rebbe must not have noticed him. Of course, it had to be an accident! How is it even possible that a rebbe could behave that way? So, he decided to go back. When he arrived, they were just finishing the evening prayers. David made his way up to the rebbe and extended his hand in greeting. Again, the rebbe simply turned away and ignored him. His worst fear confirmed and feeling dejected, David went back to his room again and cried bitterly all night. In the morning he resolved not to visit the rebbe nor pray with the community, but to leave as soon as Shabbos was over. Hours of agony and boredom went by. Eventually it was time for Shalosh Seudes, the Third Sabbath Meal toward the end of the day as the sunlight waned. He knew this was the time when Rabbi Elimelekh would be teaching, and he suddenly felt a pull to go visit him one last time, even though he had resolved not to go back. Before he knew it, he was making his way to the House of Prayer a third time. When he arrived, he stationed himself outside a window, hoping to hear a few words of Torah without having to go inside. Then he heard the rebbe say: “Sometimes a person wishes to experience the Divine Presence, and so they fast and torture themselves for six years, and then even another six years! Then they come to me to draw down the Light for which they think they have prepared themselves. But the truth is, all that fasting is like a minute drop in an ocean, and furthermore it doesn’t rise up to the Divine at all, but instead only rises to the idol of their own ego. Such a person must give all that up and go to the very bottom of their being, and begin again from there…” When David heard these words, he almost fainted. Gasping, he made his way to the door and stood motionless at the threshold. Immediately the rebbe rose from his chair and exclaimed, “Barukh Haba! Blessed is he who comes!” The rebbe rushed over to David, embraced him, and then invited him to come sit in the chair next to his at the table. The rebbe’s son Eleazar was confused by his father’s conduct, and took him aside. “Abba, why are you being so friendly? You couldn’t stand the sight of this guy yesterday!” “Oh no, you are mistaken my son – this isn’t the same person at all! Can’t you see? This is sweet Rabbi David!” David needed Rabbi Elimelekh’s fierce grace; he needed to have that soul-poisoning “scorpion” of ego slaughtered by the rebbe. Through all those years of fasting he tried to purify himself, but that’s like the ego trying to commit suicide; it doesn’t work. It’s just more ego, only a spiritualized ego. The only way out was to have that spiritual ego smashed. If we need our egos smashed, life is usually easy to oblige; this world is full of opportunities for that. That’s one path to transcendence and freedom. But there is a second path – one not of smashing our ego, but exposing it to the light of awareness, and letting it vanish on its own. Painful insults are not the only way: רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, הֱוֵי זָהִיר בִּקְרִיאַת שְׁמַע וּבַתְּפִלָּה. וּכְשֶׁאַתָּה מִתְפַּלֵּל, אַל תַּעַשׂ תְּפִלָּתְךָ קֶבַע, אֶלָּא רַחֲמִים וְתַחֲנוּנִים לִפְנֵי הַמָּקוֹם בָּרוּךְ הוּא, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר כִּי חַנּוּן וְרַחוּם הוּא אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם וְרַב חֶסֶד וְנִחָם עַל הָרָעָה. Rabbi Shimon says: Be careful in the chanting the Sh’ma and in the Prayer. When you pray, do not make your prayer a fixed form, rather, mercy and supplication before the Place, It is Blessed, as it says (Joel 2, 13): “For (the Divine is) gracious and compassionate, slow to anger, abundant in kindness, and relentful of evil.” On one hand, Rabbi Shimon says hevei zahir – be careful or meticulous with your practice. It is something we are empowered to do; we need not rely on grace. But on the other hand, al ta’as et tefilt’kha kevah – do not make your prayer a fixed form. It doesn’t seem to make sense – it just said to be careful and disciplined about it, and now it’s saying not to make it a fixed form. Then it explains: Rather, mercy and supplication before the Place – in other words, your prayer must come from your heart, from the very “bottom of your being.” On this level, it’s not a fixed form, because each time you must find your way back to your essence, and begin again from there. Then it says: וְאַל תְּהִי רָשָׁע בִּפְנֵי עַצְמְךָ And do not be wicked to yourself. That’s the Sh’ma – the affirmation of the Oneness of Being – because it means that you too are essentially part of that Oneness. You must know that however separate you seem to feel, you can find that Reality of Oneness within your own being, because It is essentially who you are. And so, while prayer takes us into humility by pointing out our ego, the Sh’ma takes us into Divinity by pointing out our Divine nature. When you have both, you have a second path for transcendence and freedom. In this week’s Torah reading there is a hint of these two paths: one through the painful destruction of ego, and the other through sincere practice: וַיְדַבֵּ֤ר יְהוָה֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה אַחֲרֵ֣י מ֔וֹת שְׁנֵ֖י בְּנֵ֣י אַהֲרֹ֑ן בְּקָרְבָתָ֥ם לִפְנֵי־יְהוָ֖ה וַיָּמֻֽתוּ׃ The Divine spoke to Moses after the death of the two sons of Aaron when they drew close before the Divine and they died. Aaron’s two sons who are killed when they approach the Divine with their “alien fires” point to the destruction of ego, just as happened in to Rabbi David Lelov (and countless other aspirants at the hands of their teachers.) This is certainly a way, though not the preferred way. The text then proceeds to outline a preferable way: וַיֹּ֨אמֶר יְהוָ֜ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֗ה דַּבֵּר֮ אֶל־אַהֲרֹ֣ן אָחִיךָ֒ וְאַל־יָבֹ֤א בְכָל־עֵת֙ אֶל־הַקֹּ֔דֶשׁ מִבֵּ֖ית לַפָּרֹ֑כֶת אֶל־פְּנֵ֨י הַכַּפֹּ֜רֶת אֲשֶׁ֤ר עַל־הָאָרֹן֙ וְלֹ֣א יָמ֔וּת כִּ֚י בֶּֽעָנָ֔ן אֵרָאֶ֖ה עַל־הַכַּפֹּֽרֶת׃ The Divine said to Moses: Speak to Aaron your brother that he is not to come at any time into the Shrine behind the curtain, in front of the cover that is upon the ark, so that he not die; for in the cloud I appear upon the cover. Aaron is instructed not to come into the Presence b’khol eit – at any time – meaning, you can’t enter the sacred through time, through the egoic perspective which sees oneself as having achieved something over time. No amount of fasting, ritual, or learning – no amount of any accumulation that happens in time can get you there. Rather, it is only in becoming naked of time that we can enter into the Presence, because the Presence is not something separate from who we are, beneath all the accumulations of ego. That is וְתַחֲנוּנִים לִפְנֵי הַמָּקוֹם רַחֲמִים – compassion and supplication before the Place. “The Place” is a Name for the Divine; it is always the Place you are now in, the space within which this moment unfolds. Its revelation is rakhamim – compassion – in response to our takhanunim – our genuine longing; in other words, it is an act of grace. At the same time, that doesn’t mean we are passive; the grace becomes available if we have the gevurah – the strength and boundaries to be zahir – to be careful and meticulous in our practice and open ourselves again anew, day by day, hour by hour, and moment by moment. In this week of Gevurah and Akharei Mot, may we renew the boundaries of our practice while going again to the depths of our essence within the space of those boundaries… More on Akharei Mot... Separate- Parshat Akharei Mot, Kedoshim

5/3/2017 1 Comment There’s something strange about this passage. God is telling the children of Israel that they should be holy without really explaining what that means, and then it says that the reason they should be holy because God is holy- ki kadosh ani Hashem Eloheikhem. So the question is, why does one follow from the other? Why should we be holy just because God is holy, and what does holy mean anyway? The word for holy, Kadosh, actually means “separate,” but not in the ordinary sense. Normally, the word “separate” connotes distance, disconnectedness, or alienation, such as when a relationship goes sour and you lose that connection with another person. But the word kadosh actually means the opposite. In a Jewish wedding ceremony, for example, we hear these words spoken between the beloveds- “At mekudeshet li- “You are holy to me…” Meaning, your beloved becomes kadosh or “separate” not because they’re separate from you, but because they’re exclusive to you. They’re your most intimate, and therefore separate from all other relationships. So, the separateness of kadosh points not to something that’s distant, but to something that’s most central. It points not to alienation, but to the deepest connection. And just as your beloved is separate from all other relationships, so too when you become present, this moment becomes separate from all other moments, and you’re able to get some distance from the world of time- from your memories about the past and your anticipations of the future. This allows you to experience yourself not as a bundle of thoughts and feelings inhabiting a body, but as the open, radiant space of awareness within which your thoughts and feelings come and go. That’s why your presence, your awareness is by its nature kadosh- separate from the world of thought and feeling within which we tend to get trapped, yet fully and intimately connected with everything that arises in this moment. So when God says kedoshim tihyu- you should be holy- it’s telling you to do the practice of holiness by becoming present- by separating your mind from the entanglements of thought and time. How is it possible for us to get free from time? Ki kadosh ani Hashem Eloheikhem- because the holiness of Being- Hashem- is already your own inner Divinity- Eloheikhem. In other words, by practicing presence, you bring forth your own deepest nature, which is holiness. This is also hinted at in the name of Parshat Akharei Mot, which means “after the death.” In order to know your own deepest nature as shamayim mima’al, the vastness of space, you have to let go of your mind-based identity- all your stories and judgments about yourself, and that can actually feel like a kind of death. But this death has an Akhar- an afterward in which your true life, the awareness that you are, becomes liberated. So on this Shabbat Akharei Mot and Kedoshim may we come to know more deeply the holiness that is felt after the death of the false self, and may we express that holiness as love and blessing to everyone we encounter. Good Shabbos! The Flower- Parshat Akharei Mot 5/3/2016 6 Comments What does it take to set your heart free? Put another way, what is it that imprisons your heart? Once I was holding a bunch of Jewish books in my hands. My three-year-old daughter came up to me and said, “Here Abba, for you!” She was trying to give me a little flower. “One moment,” I said, “let me put these books down first.” It’s like that. The heart is imprisoned by the burden of whatever is being held. Let go of what you’re holding and the heart is open to receive. There’s a little girl offering you a flower- that flower is this moment. Put down your books and receive the gift. A friend once said to me, “I always hear that I should ‘just let go.’ But what does that mean? How do I do that?” To really know how to “let go,” we have to look at why we “hold on.” There are two main reasons the mind tends to hold on to things. First, there’s holding on to the fear about what might happen. It’s true- the future is mostly uncertain, and knowing this can create an unpleasant feeling of being out of control. Holding onto time- meaning, thinking about the future- can give you a false sense of control. There’s often the unconscious belief that if you worry about something enough, you’ll be able to control it. Of course, that’s absurd, but the mind thinks that because of its deeper fear: fear of experiencing the uncertainty itself. If you really let go of your worry about what might happen, you must confront the experience of really not knowing, of being uncertain. That can be painful, and there’s naturally resistance to pain. But, if you allow yourself to experience the pain of uncertainty, it will burn away. Don’t block the pain with a “pile of books”- that is, a pile of stories about what might be. On the other side of this pain is liberation- the expansive and simple dwelling with Being in the present. Second, there can be some negativity about what might have happened in the past. If you let go of your preoccupation with time, if you let go of whatever “happened,” you must confront the fact that the past is truly over. The deeper level of this is confronting your own mortality. Everything, eventually, will be “over.” But, let go of the past, and feel the insecurity of knowing that everything is passing. Don’t block that feeling of insecurity with a “pile of books”- with narratives about days past. Then you will see- there’s a gift being offered right now. It is precious; it is fragile- a flower offered by a little child, this precious moment. This week’s reading, Parshat Akharei Mot, begins with a warning to Aaron the Priest concerning the rites he is to perform on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement: “V’al yavo b’khol eit el hakodesh- “He shall not come at all times into the holy (sanctuary)…” We may try to reach holiness by working out the past in our minds, or by insisting on a certain future, but as it says- “V’al yavo b’khol eit… he shall not come at all times…” In other words, you cannot enter holiness through time! To enter the holy, you must leave time behind, and enter it Now. Let your grasping after the future burn, let your clinging to the past be released. As it says, continuing the description of the Yom Kippur rite- “V’lakakh et sh’nei hasirim- “He shall take two goats…” Letting go of time means letting go of past and future- one goat for the past, one for the future. The first goat, it goes on top describe, is “for Hashem”- meaning, the future is in the hands of Hashem. This goat is slaughtered and burned. Meaning: experience the burning of uncertainty and slaughter your grasping after control. The other goat is “for Azazel.” The word Azazel is composed of two words- “az” means “strength”, and “azel” means “exhausted, used up”. In other words, the “strength” of the past is “used up.” The past is gone, over, done. Let it go, or it will use you up! This goat is let go to roam free into the wilderness. The past is gone, the future is in the hands of the Divine. But those Divine hands are not separate from your hands. Set your hands free- put down the narratives- and receive the flower of this moment, as it is, and with all its creative potential for what could be… There’s a story that once Reb Yehezkel of Kozmir strolled with his young son in the Zaksi Gardens in Warsaw. His son turned to him with a question- “Abba, whenever we come here, I feel such a peace and holiness, unlike I feel anywhere else. I would expect to find it when I’m studying Torah, but instead I feel it here.” Reb Yehezkel answered- “As you know, it says in the Prophets- ‘M’lo khol ha’aretz k’vodo- the whole world is filled with the Divine Glory.’ But, sometimes we’re blocked from recognizing it.” “But Abba,” pressed his son, “Why would I be blocked from feeling the Divine Glory when I’m learning Torah? And why would I feel it so strongly in this non-religious place?” “Let me tell you a story,” answered the rebbe. “In the days before Reb Simhah Bunem of Pshischah evolved into great tzaddik, he would commute to the city of Danzig and minister to the community there, even though he lived in Lublin. “When he returned to Lublin, he would always spend the first Shabbos with his rebbe, the “Seer”- Reb Yaakov Yitzhak of Lublin. “One time when he arrived back at Lublin, he felt disconnected from the holiness he had felt while he was in Danzig. To make matters worse, the Seer wouldn’t give him the usual greeting of “Shalom,” and in fact behaved rather coldly to Reb Simha. “Figuring this was just a mistake, he returned to the Seer some hours later, hoping to get a blast of the rebbe’s spiritual juice, but again the Seer just ignored him. He left feeling dry and sad that his rebbe had rejected him. “Then, a certain Talmudic teaching came to his mind: that a person beset with unexpected tribulations should scrutinize their actions. “So, he mentally scrutinized every detail of his conduct in Danzig, but he couldn’t recall anything he had done wrong. If anything, he noted with satisfaction that this visit was definitely of the kind that he liked to nickname ‘a good Danzig,’ for he had brought down such holy ecstasy in the prayers and chanting. “But then he remembered the rest of the teaching. It goes on to say- ‘Pishpeish v’lo matza, yitleh b’vitul Torah- ‘If he sought and did not find, let him ascribe it to the diminishing (bitul) of Torah.’ “Meaning, that his suffering must be caused by having not studied enough. “Taking this advice to heart, Reb Simhah decided to start studying right then and there. Opening his Talmud, he sat down and studied earnestly all that day and night. “Suddenly, a novel light on the Talmudic teaching dawned on him. He turned the words over in his mind once more: ‘Pishpeish v’lo matza, yitleh b’vitul Torah.’ “He began to think that perhaps what the sages really meant by their advice was not that he didn’t study enough, but that he wasn’t ‘diminished’ (bitul) by his studying. Rather than humbling himself with Torah, all that book knowledge was simply building up his own ego, and blocking his connection with the Presence. As soon as he realized this, he ‘let go’ of the books- he let go of being a great scholar, and the Presence that he longed for returned. “Later that evening, the Seer greeted him warmly: ‘Danzig, as you know, is not such a religious place, yet the Divine Presence is everywhere, as it says- the whole world is filled with Its Glory. If, while you were there, the Divine Presence rested upon you, this was no great feat accomplished by your extensive learning- it was because in your ecstasy, you opened to what is always already here.’” On this Shabbos Akharei Mot, the “Sabbath After the Death,” may all that we hold out of pride drop away. May all that we hold out of fear drop away. May all that we hold in an attempt to control drop away… and may we live in this holiness that is always already here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed